Long Time So Long (Photographs)

2022, inkjet prints, varied dimensions

Humour is often used as a tool to express discontentment with those in power, to challenge norms and to say the unsayable. Humor is present in traditions like Talchum, a Korean mask dance that tells stories of social rebellion, and in contemporary digital communications like memes and emojis. In merging these two sources, the artist creates a provocative images that references these practices of resistance, both ancient and new.

Untitled 6 (Long Time So Long) and Untitled 7 (Long Time So Long), 2022, (installation view), inkjet prints, 139.7 x 111.8 cm (55 x 44 inches) each, The Image Centre, Photo credit: James Morley

Untitled 6 (Long Time So Long), 2022, inkjet print, 139.7 x 111.8 cm (55 x 44 inches)

Untitled 7 (Long Time So Long), 2022, inkjet print, 139.7 x 111.8 cm (55 x 44 inches)

Bringing together the pre-modern and the futuristic, Long Time So Long’s masks mash up the ubiquitous emojis we use to set the tone of our digital relationships and characters from

talchum, traditional Korean dances that tell stories of social rebellion against a dominant order. Through their saturated colour and exaggerated expressions, the masks express an extreme intensity, while the figure wearing them adopts casual poses as if this intensity is the most natural thing in the world. In a costume made of space-age fabric appliquéd onto unbleached cotton, the figure appears in different masks on and around a seven-and-a-half-kilometre sewage pipe hidden within a jetty extending off BC’s Iona Island.

Iona Island’s history is one of environmental ruination and colonial atrocities, but it is also the site of a semi-successful political protest and a reclamation project. Today, in addition to the sewage plant, it is home to a park and bird sanctuary.

Untitled 1 (Long Time So Long), 2022, inkjet print, 139.7 x 111.8 cm (55 x 44 inches)

Untitled 1 (Long Time So Long) and ChronoChrome 2 (Long Time So Long), 2022, (installation view), inkjet prints, varied dimensions, The Image Centre, Photo credit: James Morley

ChronoChrome 2 (Long Time So Long), 2022, inkjet print,182.9 x 121.9 cm (72 x 48 inches)

In this photograph, a figure wearing a silver mask stands on an endless road. Reflected in the mask is the image behind the camera: a continuation of the road, receding into the distance. In a tunnel-like form beside the road is a concrete jetty that houses a sewage pipe, the literal and psychic underbelly of Iona Island, where the long shadows of histories intermingle.

Before it was a sewage plant, Iona Island was ancestral territory that supported 9,000 years of Musqueam history. When it built the plant in the 1950s, the British Columbia government paid

one dollar to lease (in perpetuity) a portion of the Musqueam reserve to run the pipe. The plant treats sewage from municipalities outside Richmond, where Iona Island is located. Protests from

the people of Richmond were not able to prevent the plant from being built; however, extreme pollutant limits were imposed on the developers by cleverly declaring the island a nature reserve.

Acknowledging the past and turned towards the future, ChronoChrome 2 presents an image from the pivot of time.

ChronoChrome 1 (Long Time So Long), 2022, inkjet print, 139.7 x 203.2 cm (55 x 80 inches)

Untitled 8 (Long Time So Long), 2022, inkjet print, 139.7 x 203.2 cm (55 x 80 inches)

Untitled 5 (Long Time So Long), 2022, inkjet print, 139.7 x 111.8 cm (55 x 44 inches)

Untitled 8 (Long Time So Long) and Untitled 5 (Long Time So Long), 2022, (installation view), inkjet prints, varied dimensions, The Image Centre, Photo credit: James Morley

Untitled 2 (Long Time So Long), 2022, inkjet print, 139.7 x 111.8 cm (55 x 44 inches)

Untitled 9 (Long Time So Long), 2022, inkjet print, 139.7 x 203.2 cm (55 x 80 inches)

Untitled 2 (Long Time So Long), Untitled 9 (Long Time So Long) and Hin Saek Piper 1 (Long Time So Long), 2022, (installation view), inkjet prints, varied dimensions, The Image Centre, Photo credit: James Morley

Hin Saek Piper 1 (Long Time So Long), 2022, inkjet print, 152.4 x 228.6 cm (60 x 90 inches)

Long Time So Long emerges from the experiences of many Canadians during the pandemic: the forced isolation, the strange sense of time, and the anxiety of living under constant threat

while going about our quotidian lives.

The mask worn in this photograph is hin saek (“white,” the funerary colour in Korea). With a mouth made of three fluted orifices, the work seems to be haunted by both COVID spikes and the Pied Piper. In the 13th century, the German town of Hamelin called upon the Piper to play his magic flute to lead away the rats that were causing plague. When the citizens refused to pay

him, according to legend, he led the children of the town away as well.

This photograph seems to elicit a feeling of impending doom, one connected to the rising death counts from COVID, increasing environmental devastation, and the growing hatred in our

contemporary moment. Who will pay the piper?

Untitled 4 (Long Time So Long), 2022, inkjet print, 139.7 x 111.8 cm (55 x 44 inches)

Untitled 3 (Long Time So Long), 2022, inkjet print, 139.7 x 111.8 cm (55 x 44 inches)

Untitled 10 (Long Time So Long), 2022, inkjet print, 139.7 x 111.8 cm (55 x 44 inches)

Regeneration 1 (Long Time So Long), 2022, inkjet print, 45.7 x 57.2 cm; mat border: 7.6 cm on three sides plus 8.9 cm on bottom (18 x 22.5 inches; mat border: 3 inches on three sides plus 3.5 inches on bottom)

Regeneration 2 (Long Time So Long), 2022, inkjet print, 45.7 x 57.2 cm; mat border: 7.6 cm on three sides plus 8.9 cm on bottom (18 x 22.5 inches; mat border: 3 inches on three sides plus 3.5 inches on bottom)

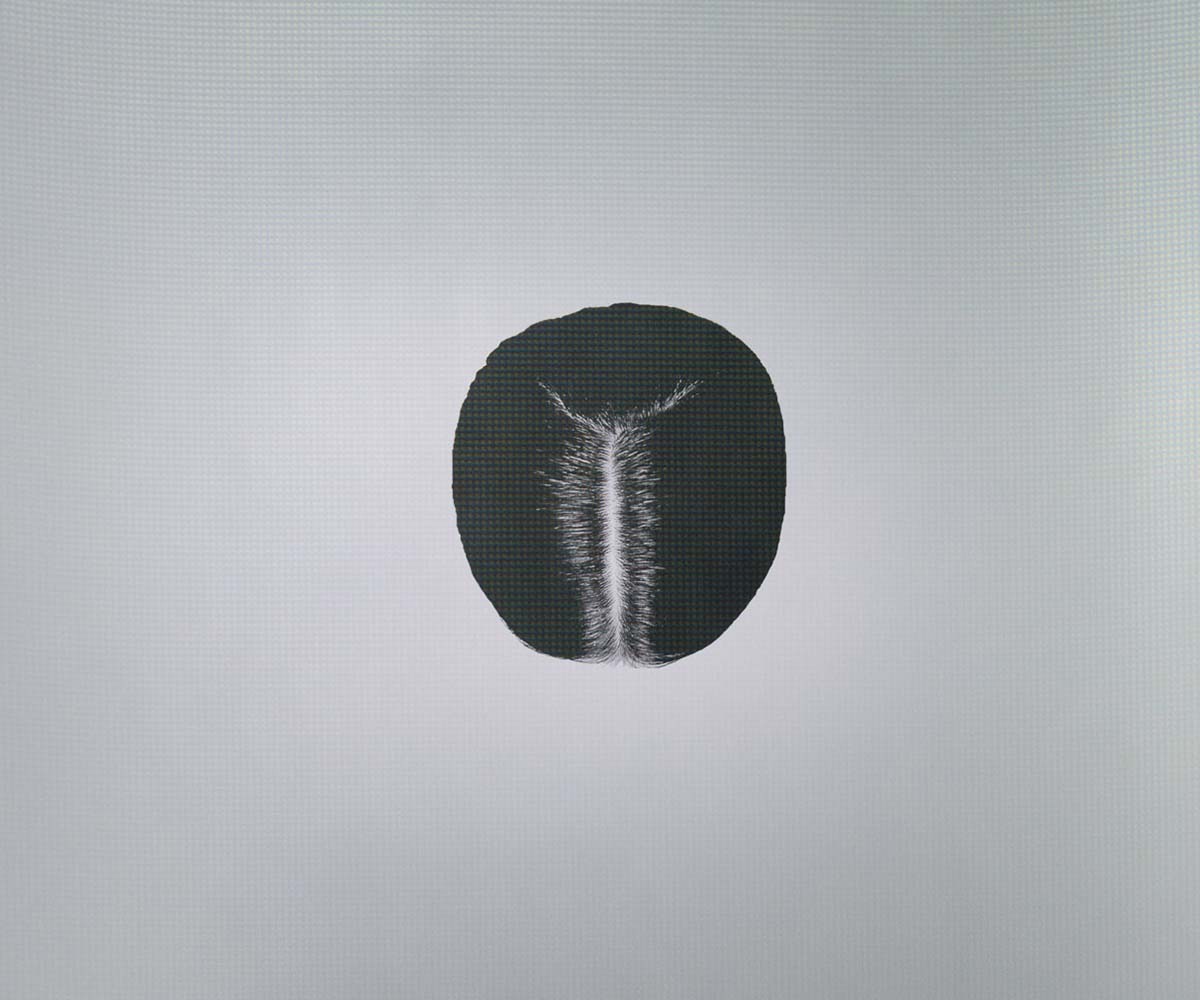

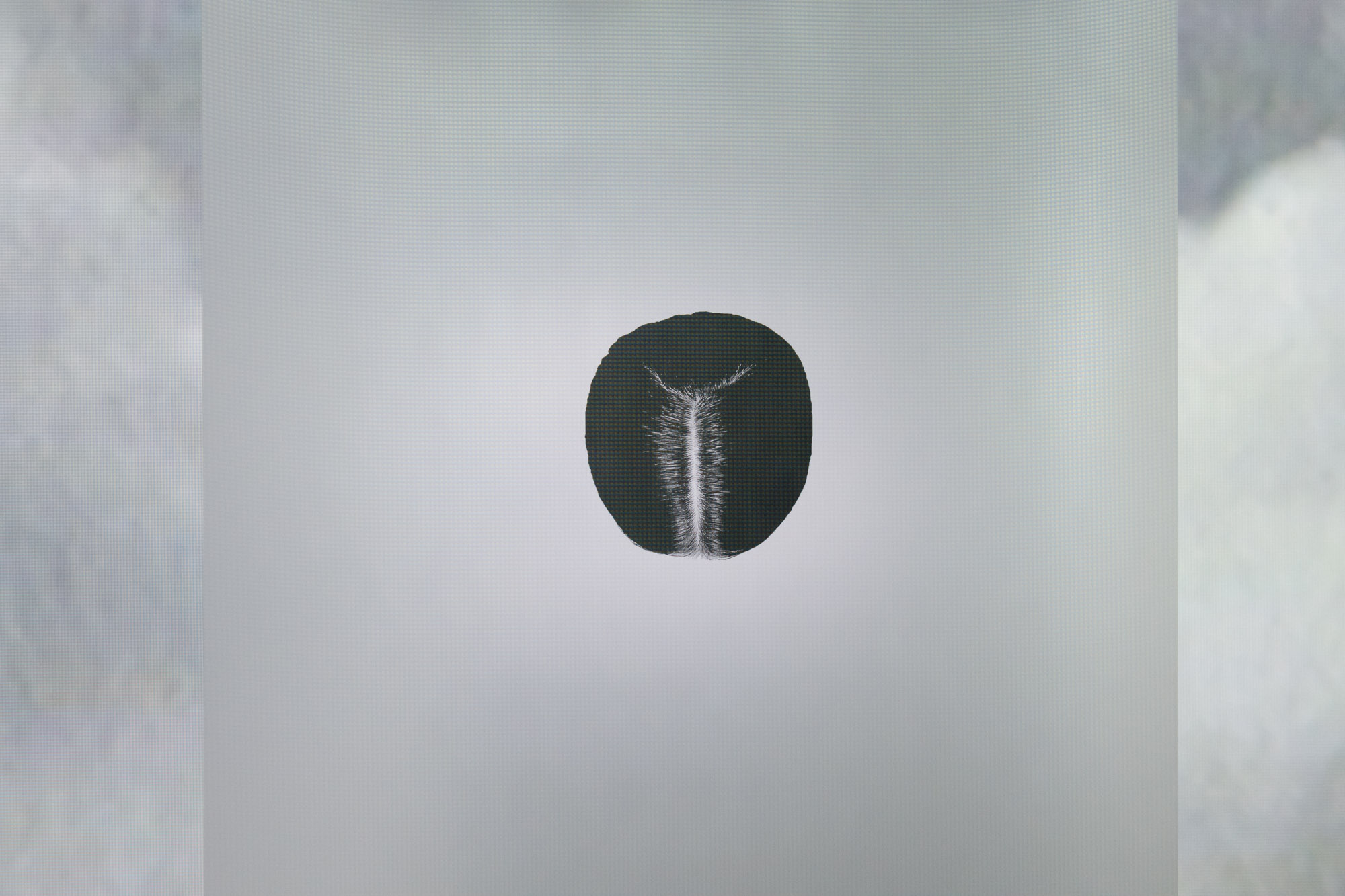

Prosthetic Portal

2022, inkjet prints, 152.4 x 152.4 cm (60 x 60 inches) each

Our collective body has a face that, like all faces, is both a screen that others project onto and a mirror that reflects our selves. The inflection point between the two is where we meet. Here, into the cotton padding of the back of the masks, Yoon has inserted countless acupuncture needles, conduits for the transfer of energy, or qi (ki). These needles in particular carry a history of this transfer; they have previously been used to heal. In Prosthetic Portals, Jin-me Yoon articulates a poetics of repair.

Prosthetic Portal 4, 2022, (installation view), inkjet print, 152.4 x 152.4 cm (60 x 60 inches), Evergreen Cultural Centre, photo credit: Rachel Topham

Prosthetic Portal 4, 2022, inkjet print, 152.4 x 152.4 cm (60 x 60 inches)

Prosthetic Portal 3, 2022, inkjet print, 152.4 x 152.4 cm (60 x 60 inches)

Prosthetic Portal 2, 2022, inkjet print, 152.4 x 152.4 cm (60 x 60 inches)

Inside Broken Worlds, Prosthetic Portal 3, and Prosthetic Portal 2, 2022, (installation view), inkjet prints, 152.4 x 152.4 cm (60 x 60 inches) each, The Image Centre, Photo credit: James Morley

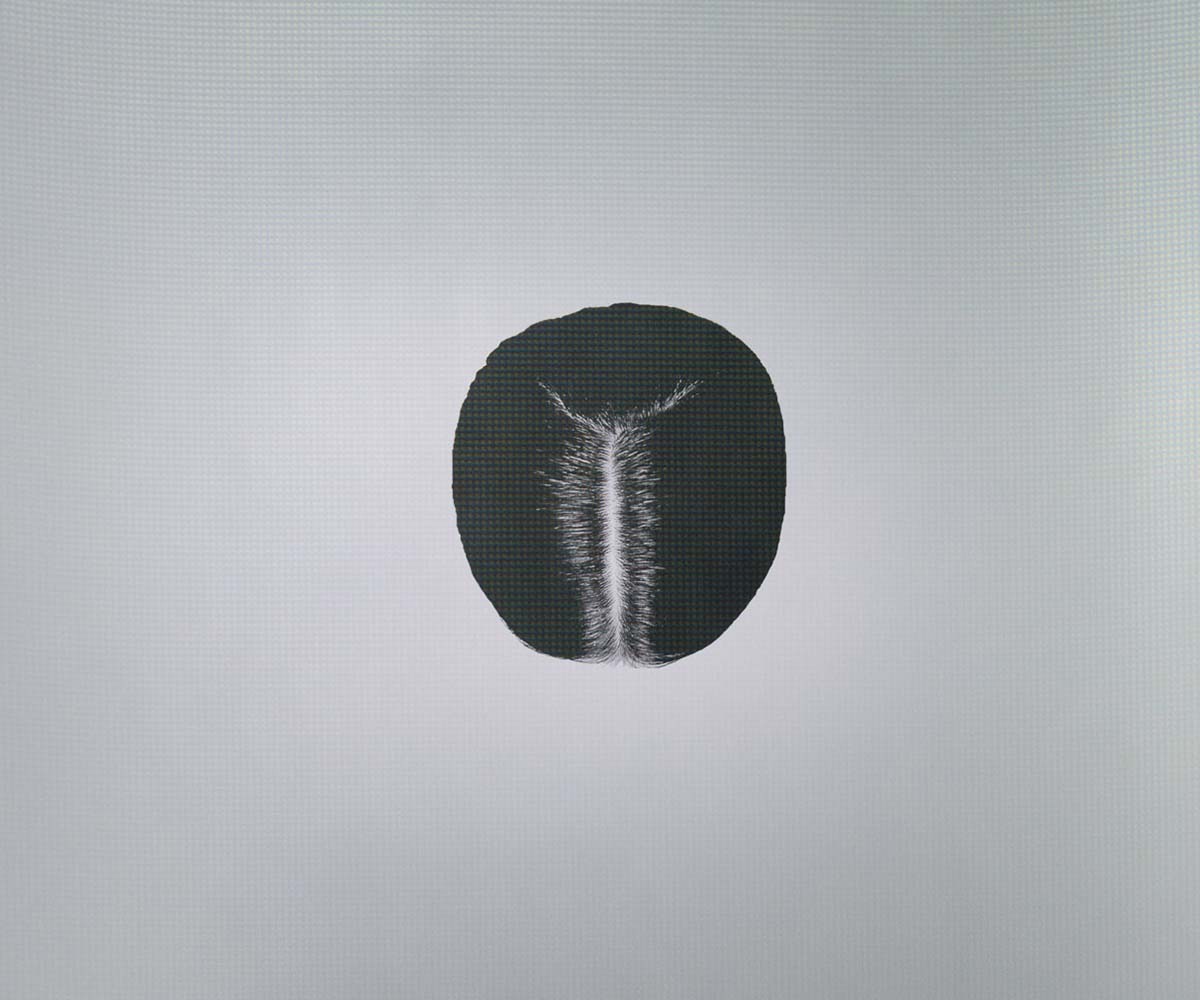

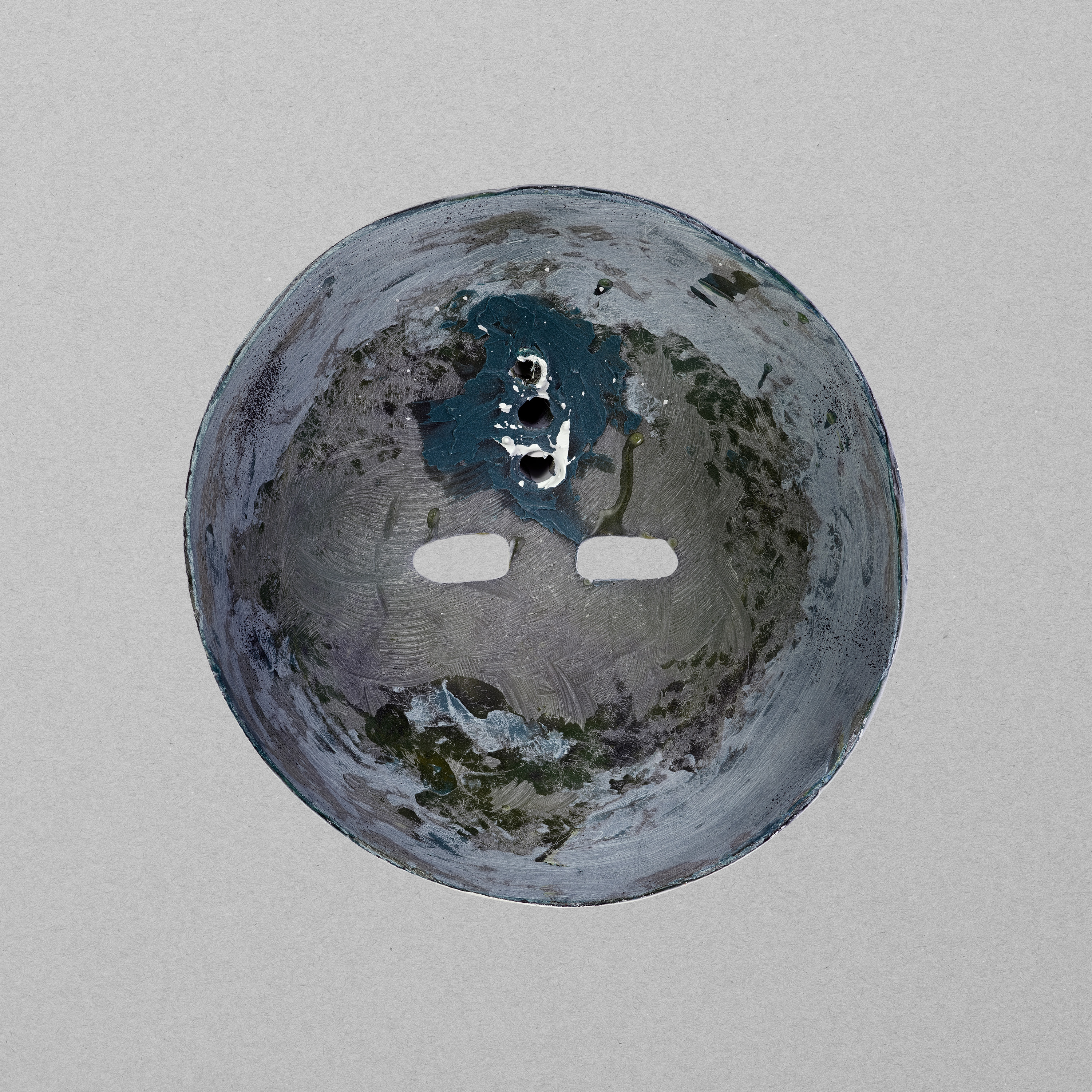

Inside Broken Worlds

2022, inkjet print, 152.4 x 152.4 cm (60 x 60 inches)

As the verso of the Hin Saek Piper mask, this image is a response to the extremity of the social, political, economic, and environmental landscape today, an extremity due in part to the threatened state the pandemic has put us all into. Inside Broken Worlds points to the virus that has weakened not just our physical but also our social immune systems. Secondary infections have raged in our collective body for years, and with weakened immunity, they suddenly boil to the surface. Our collective body has a face that, like all faces, is both a screen that others project onto and a mirror that reflects our selves.

Inside Broken Worlds, 2022, inkjet print, 152.4 x 152.4 cm (60 x 60 inches)

Inside Broken Worlds, 2022, (installation view), inkjet print, 152.4 x 152.4 cm (60 x 60 inches), The Image Centre, Photo credit: James Morley

Long Time So Long (Video)

2023, single-channel video, 19:02

Long Time So Long is both a political and psychic landscape as well as a real one set on unceded Musqueam territory known as Iona Beach Regional Park in Richmond, BC. Today, in addition to a sewage plant, Iona Island is home to a park and bird sanctuary, established following a political protest and reclamation project. Its history, though, is one of environmental ruination and colonial atrocity. Made during the pandemic, this surreal and uncanny video holds in tension an expression of sadness for the past as well as restrained hope for the future.

Draped in white – the funerary colour in Korean traditional culture – the figure wears 2 masks: one a mirrored surface that reflects the surrounding world, and the other a “hin saek”/white face with holes for eyes and three fluted orifices for a mouth. Alone and multiple, the figure walks out into the stark shifting estuarian landscape that is oil blackened, white and frozen and richly hued of blue-mauves as if ancient and futuristic at once. With a resonant haunting soundscape composed of percussive crackling, droning and human humming, the unreal drag of time and the distortion of existential isolation is amplified.

Long Time So Long, 2023, (video still), single-channel video, 19:02

Somatic Soundings (Long Time So Long)

2023, 24-channel soundscape

At the time of recording, this chorus of incongruous melodies gave way to a healing process for participants in a somatic workshop. Now, in the gallery, separated from the original experience, the sounds produce a haunting, cacophonic chamber of murmurs and soothing tones. Hypnotic in its meditative droning, the soundscape is oceanic and expansive, presenting an experience that is equally comforting and unsettling. The intangible waves of sound aim to permeate layers of the body and memory, bypassing language to articulate a profound sense of the inner self. The assembly of singular voices also acts as a reminder of the depth of shared communal experiences that connect us to the exterior world, both social and cosmic.

- Katherine Dennis, Art Gallery at Evergreen

Somatic Soundings (Long Time So Long), 2023, (installation vview), 24-channel soundscape, various durations, Evergreen Cultural Centre, photo credit: Rachel Topham

Somatic Soundings (Long Time So Long), 2023, (installation view), 24-channel soundscape, various durations, Evergreen Cultural Centre, photo credit: Rachel Topham

Listening in Place

2022, chromogenic prints mounted on Dibond

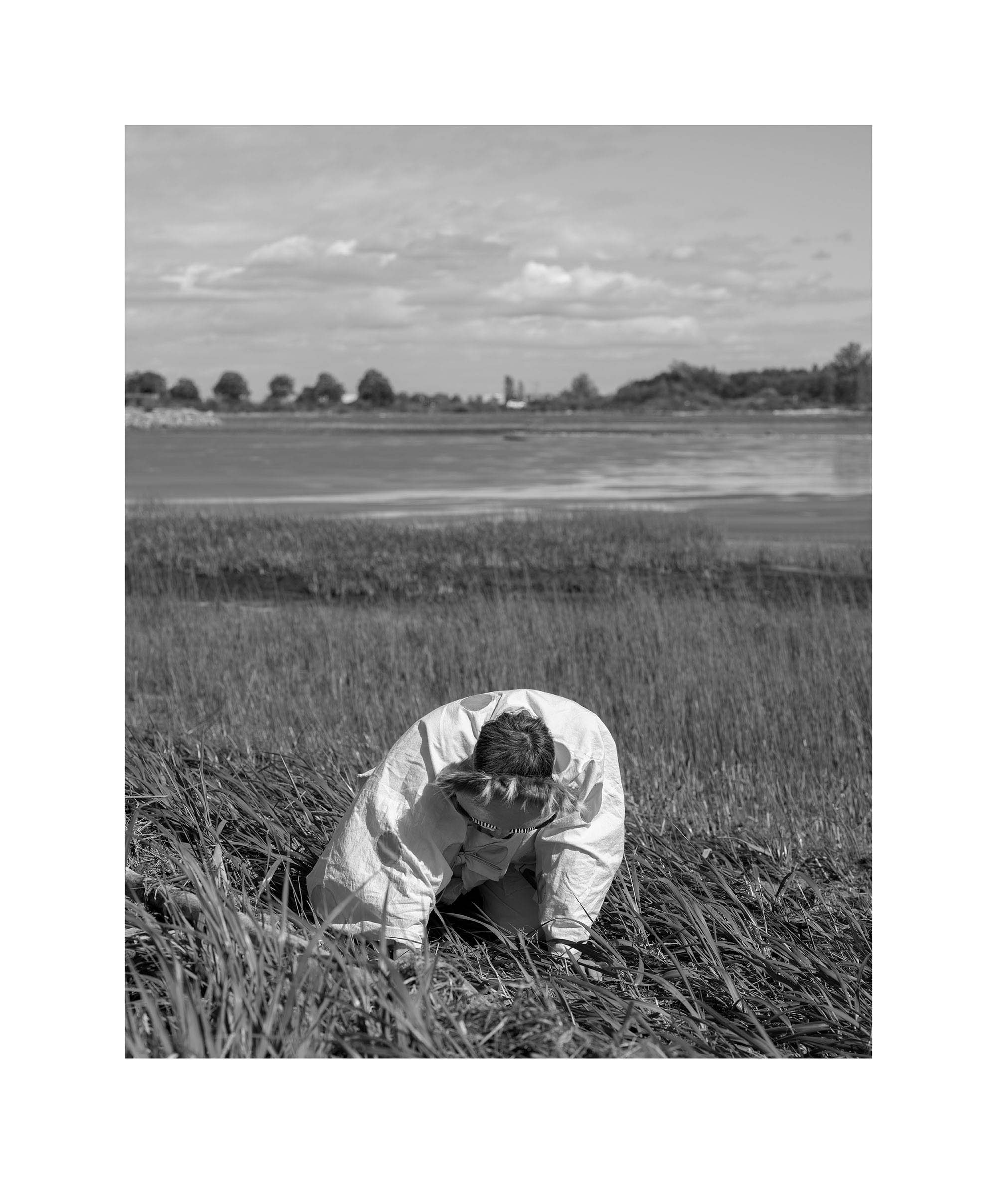

As a part of the series titled Listening in Place, these 3 images were shot in Vanier Park in what is now known as Vancouver. Formerly a site of the Royal Canadian Airforce (RCAF) station, currently Vanier Park is now a place of tourism and leisure. The activities that take place on this land do so on top of a history of violent land dispossession, as told to Yoon by Találsamkin Siyám Bill Williams, a hereditary chief of the Squamish Nation. Vanier Park was historically the land of the ancestral Squamish settlement of Sen̓áḵw, which was burned to the ground by the provincial government, displacing the families therein.

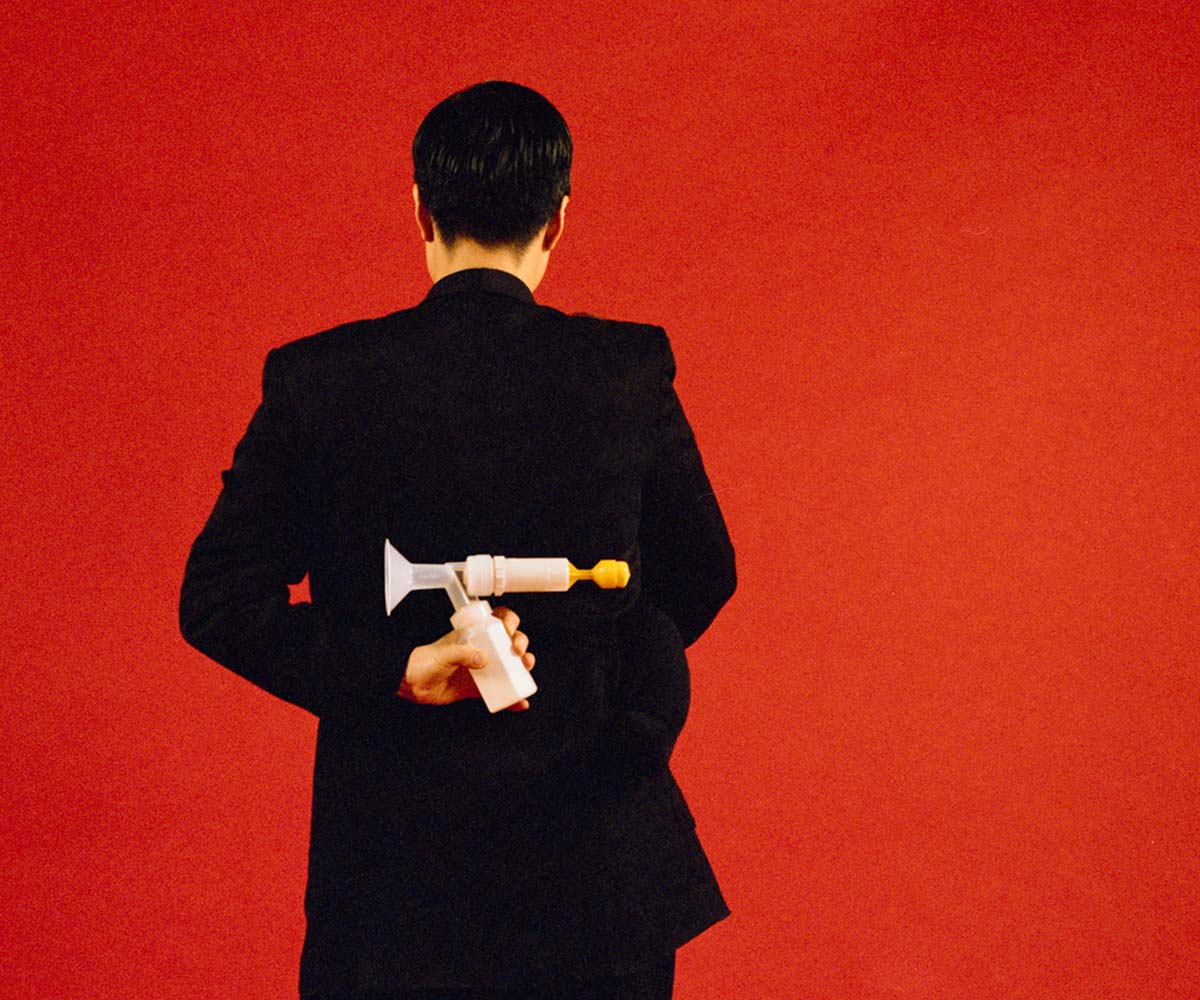

This work expresses her direct learning of these histories, both politically and aesthetically: “to embody land acknowledgements is to listen, to look differently.” In Longer View the artist replaces binoculars, an apparatus of ocular enhancement with a prosthetic prop that alludes to other ways of seeing, ways that for Yoon are linked to listening. Attunement Above and Below is a diptych. One image is of a microphone placed in front of a large Weeping Beech, a tree of European origin with networks below the earth. The second image is of the artist squatting using the same prosthetic prop – this time held up to her ears in what seems to be an absurdist dadaist gesture – listening to the ground suggesting the importance of being attuned to both the immediately visible as well as the invisible lying beneath the surface.

Longer View (Listening In Place), 2022, chromogenic print mounted on Dibond, 83.8 x 128.3 cm (33 x 50.5 inches)

Attunement Above and Below (Listening in Place) 1, 2022, chromogenic print mounted on Dibond, 83.8 x 128.3 cm (33 x 50.5 22 x 33.6 inches)

Attunement Above and Below (Listening in Place) 2, 2022, chromogenic print mounted on Dibond, 55.9 x 85.4 cm (22 x 33.6 inches)

Mul Maeum (Video)

2022, three-channel video

Mul Maeum transverses three locations on the Korean peninsula to explore the consequences of extraction economies and military industry on the livelihood and lifeways of people, nature and marine environments. One location is a fishing village near Saemangeum, home to the world’s longest seawall. The construction of the thirty-three-kilometre wall has displaced the estuarine tidal flat that was once the natural habitat for migratory birds. The second location is the village of Gangjeong on Jeju Island, where the construction of a naval base has disrupted the sacred Gureombi rock. In Gangjeong, we encounter a Yemeni family, refugees who the artist met during an earlier research trip. The third site is the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) separating North and South Korea—ironically also one of the most richly bio-diverse areas in the region. Intercutting these three sites across three screens, Jin-me Yoon’s work flows like water calling up the title Mul Maeum, which directly translates as “Water, Mind-heart.”

- Diana Freundl, Vancouver Art Gallery

Mul Maeum, 2022, (installation view), three-channel video, 30:48, Vancouver Art Gallery, photo credit: Ian Lefebvre and Kyla Bailey

Mul Maeum, 2022, (installation view), three-channel video, 30:48, Vancouver Art Gallery, photo credit: Ian Lefebvre and Kyla Bailey

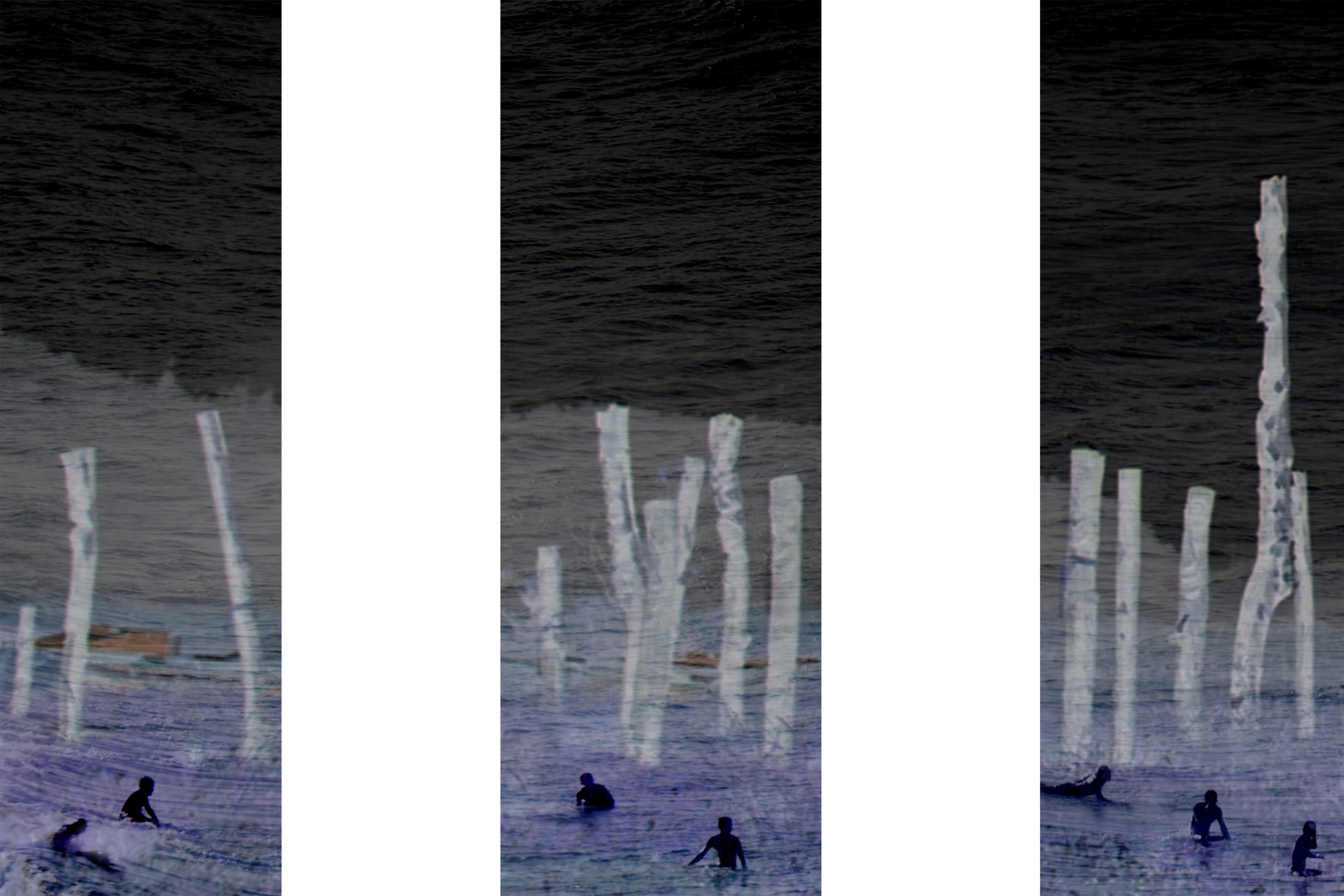

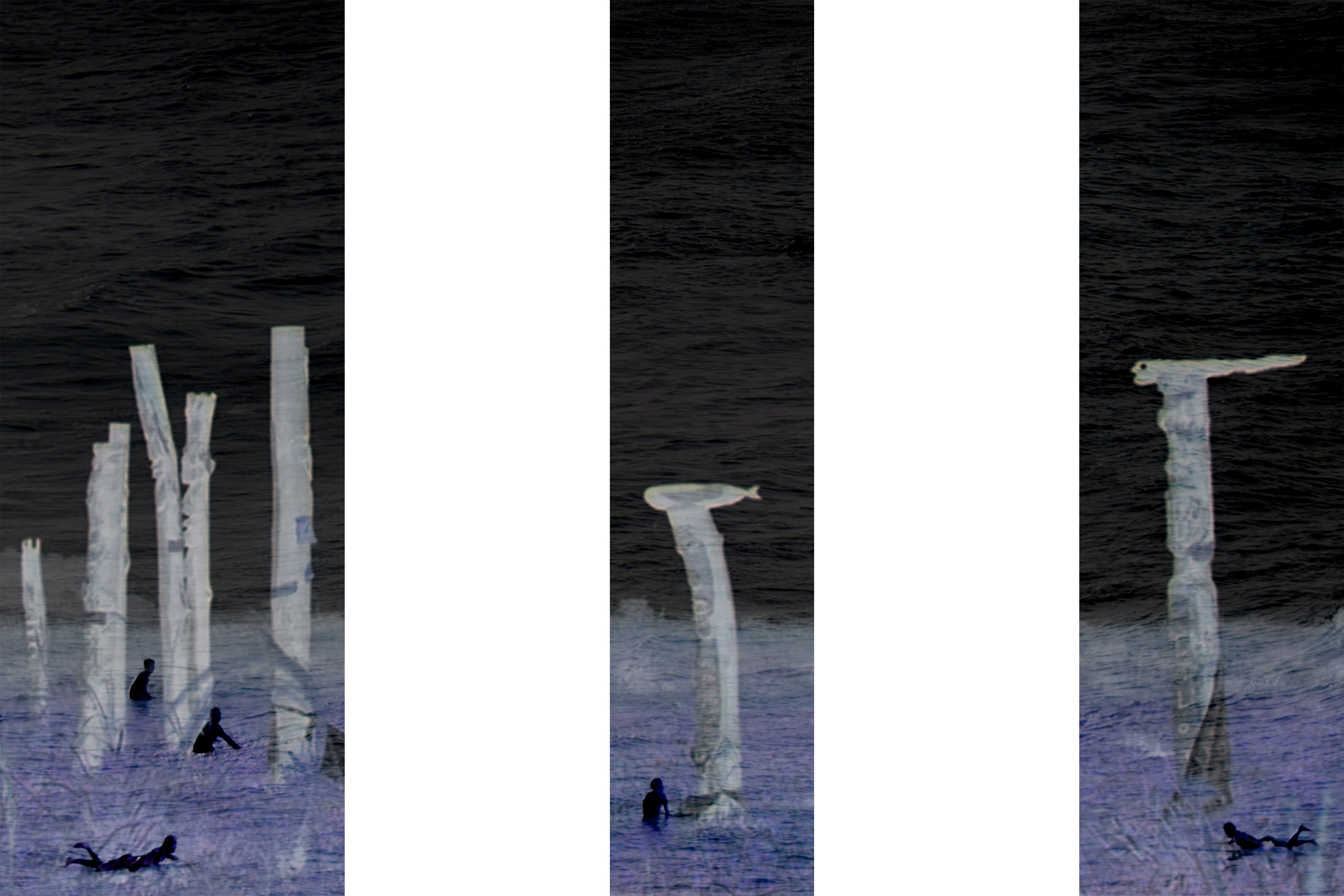

Still So (Mul Maeum)

2022, inkjet print on bond paper

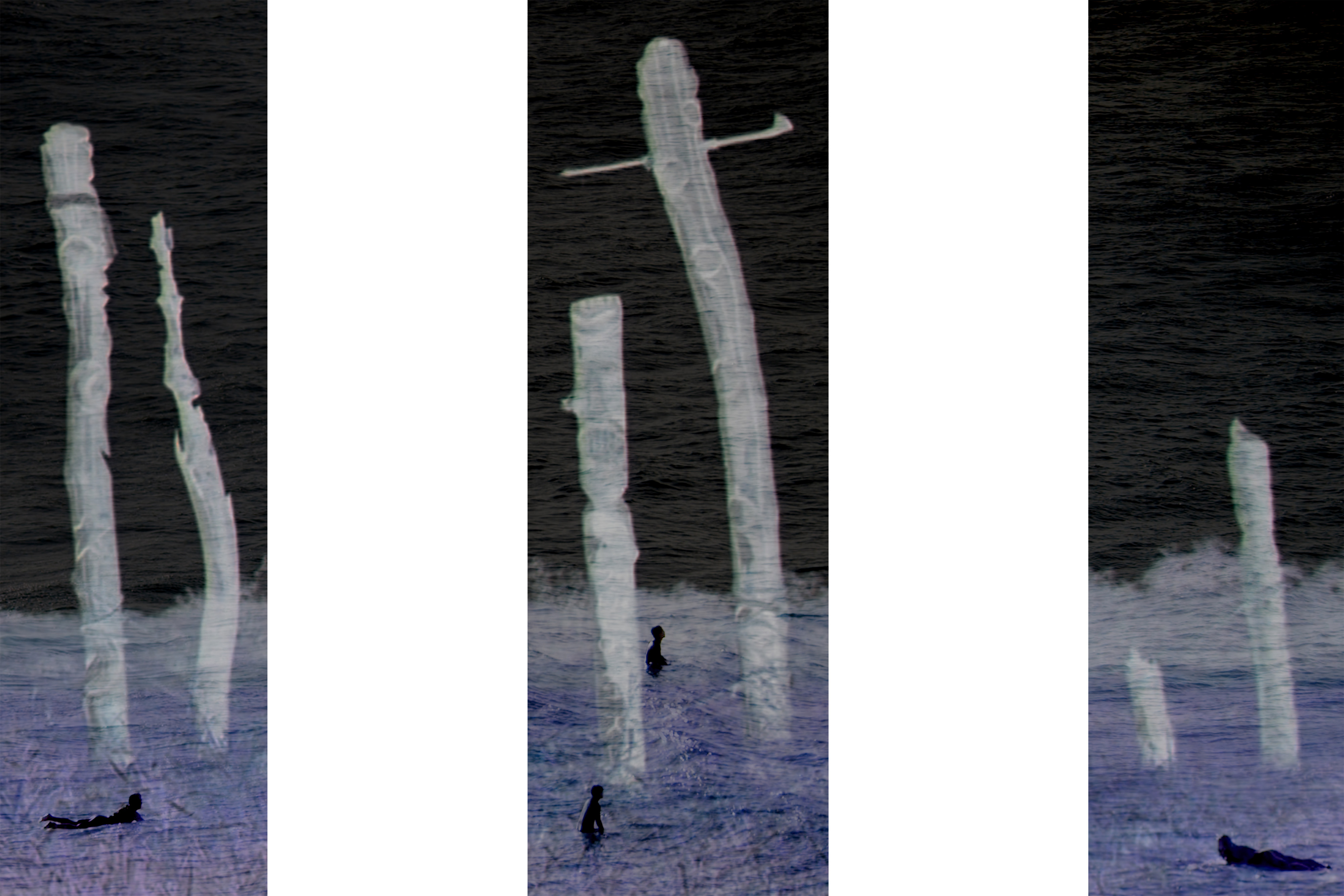

Still So (Mul Maeum) is comprised of nine scroll-like prints depicting jangseungs (Korean totem poles). These poles were made by activists resisting the building of the world’s longest seawall in Saemangum, which disrupted a major estuarine tidal flat, destroying the natural habitat for migratory birds. Located in Jin-me Yoon’s ancestral province, this seawall—stretching along South Korea’s southwest coast—dried out the land, endangered birds and displaced whole fishing communities. The jangseungs stand tall: raised by the activists as reminders of the once life-sustaining estuary, buried over by the Saemangum reclamation project. Here, in their haunted form as negative images, they now mark the loss of one of Asia’s most important wetlands and all that is lost along with it.

- Diana Freundl, Vancouver Art Gallery

Still So (Mul Maeum), 2022, (installation view), nine inkjet prints on bond paper, varied dimensions: 243.8 x 58.9 cm to 243.8 x 92.2 cm, Vancouver Art Gallery, photo credit: Ian Lefebvre and Kyla Bailey

Still So (Mul Maeum), 2022, (detail, 1 - 3), nine inkjet prints on bond paper, varied dimensions: 243.8 x 58.9 cm to 243.8 x 92.2 cm

Still So (Mul Maeum), 2022, (detail, 4 - 6), nine inkjet prints on bond paper, varied dimensions: 243.8 x 58.9 cm to 243.8 x 92.2 cm

Still So (Mul Maeum), 2022, (detail, 7 - 9), nine inkjet prints on bond paper, varied dimensions: 243.8 x 58.9 cm to 243.8 x 92.2 cm

Listening Place (Under Burrard Bridge)

2022, chromogenic print

In this photograph with its single-point perspective, a mammoth bridge with repeating concrete arches appears to recede into history. Under the arches, people in camp chairs look small in relation to the built form. Seated there are Chung-soon Yoon and Hereditary Chief Találsamkin Siyám Bill Williams of Sḵwx̱wú7mesh Úxwumixw (Squamish Nation), representatives of two different cultures colonized by others. One chair is left empty for the ancestors; seated in the other two are adult children from each family. To this intimate intergenerational group Chief Bill recounts the colonialist crimes upon which the structure was built: the dispossession, the forced dislocation, the attempted eradication of a people and the burning of their homes. The bridge testifies to the naturalization of the past’s vision of “progress”; the photograph documents a witnessing of that past—a listening place.

Listening Place (Under Burrard Bridge), 2022, (installation view), chromogenic print, 81.3 x 121.9 cm (32 x 48 inches), The Image Centre, Photo credit: James Morley

Turning Time (Pacific Flyways)

2022, 18-channel video installation

Against the backdrop of Burnaby Mountain, youth of Korean ancestry are seen moving meditatively, using gestures inspired by the Crane Dance, a traditional Korean folk dance. Cranes are one of many symbols in Korean culture that indicate longevity, life, ancestors and cultural traditions. Working with the same group of youth featured in A Group for 2067, Jin-me Yoon films them within the natural and industrial landscape of a bird sanctuary on Maplewood Flats, located on the unceded lands and waters of the Tsleil-Waututh and Coast Salish peoples. The video reflects on the complex entangled histories of land, both ancestral and environmental. Ultimately, this work asks if it is possible to explore other ways of coexisting among humans and non-humans that value traditional knowledge in light of the contemporary climate catastrophe. A coexistence that would generate new potential futures.

- Diana Freundl, Vancouver Art Gallery

Turning Time (Pacific Flyways), 2022, (installation view), 18-channel video installation, dimensions variable, varied durations: 9:33 to 15:23 minutes, Vancouver Art Gallery. Photo credit: Ian Lefebvre

Turning Time (Pacific Flyways), 2022, (installation detail), 18-channel video installation, dimensions variable, varied durations: 9:33 to 15:23 minutes, Vancouver Art Gallery. Photo credit: Ian Lefebvre

A Group for 2067 (Pacific Flyways)

2022, 18 inkjet prints

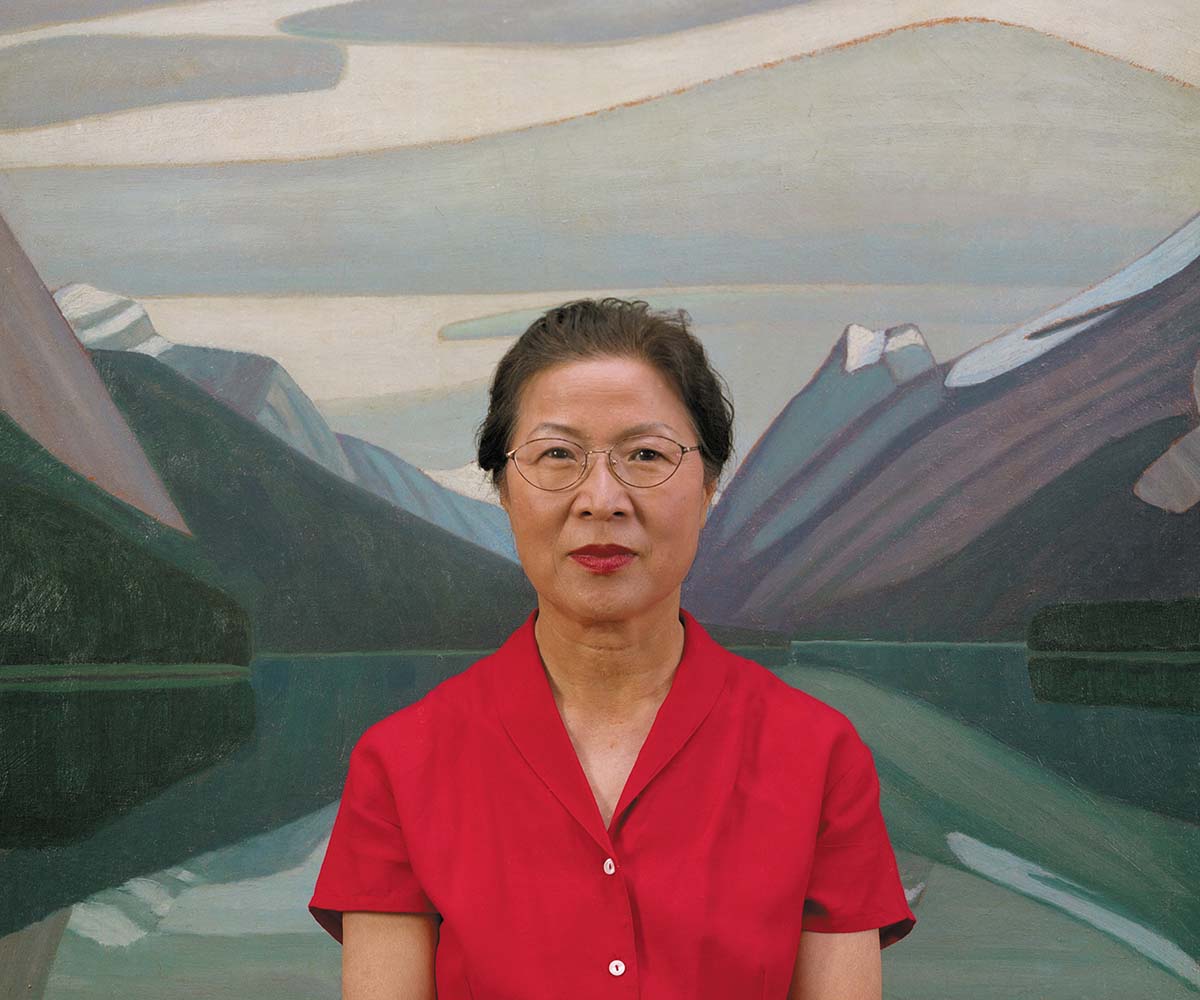

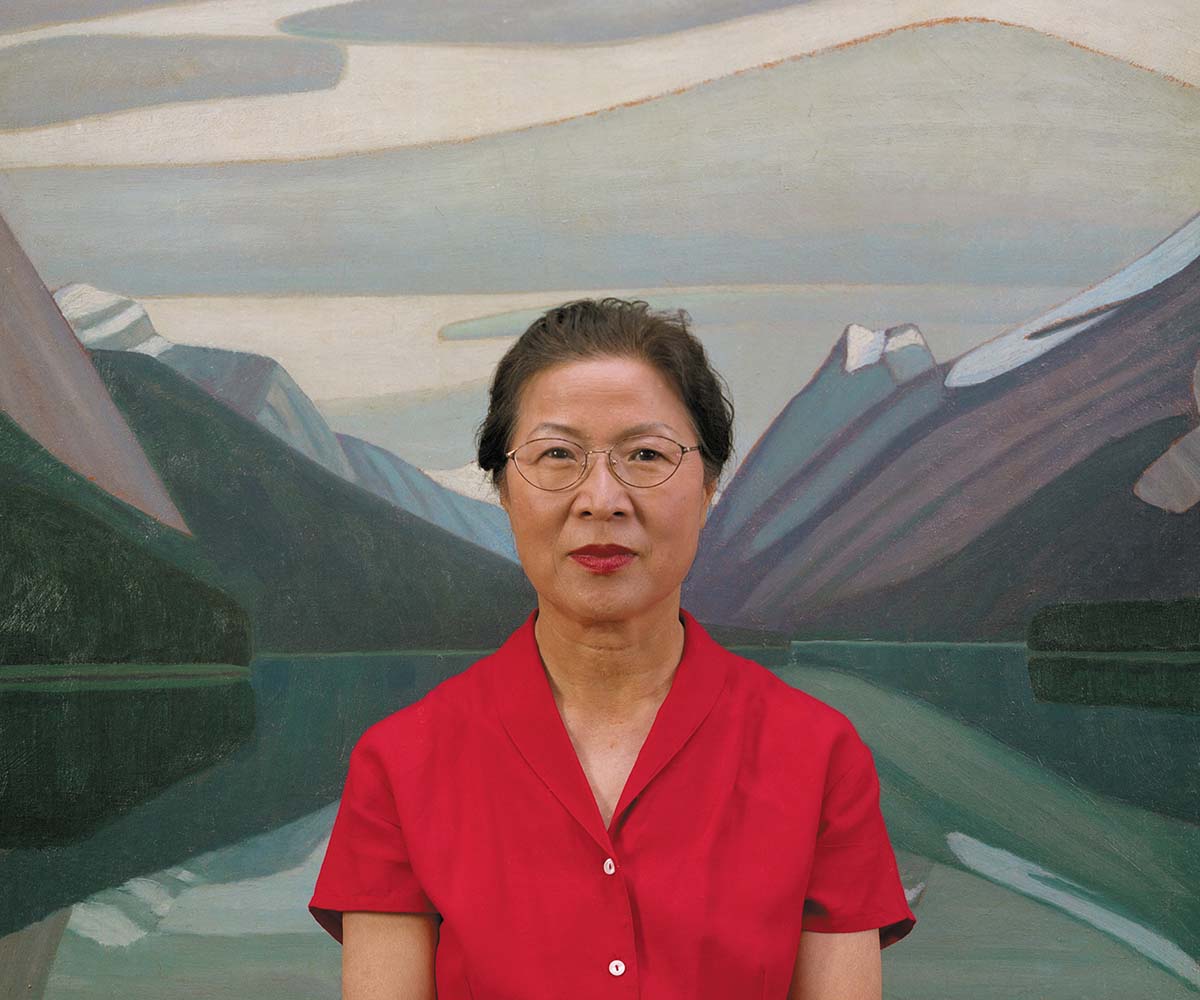

A Group for 2067 (Pacific Flyways) cites Jin-me Yoon’s earlier iconic photo work A Group of Sixty-Seven (1996), which is comprised of two sets of portraits of sixty-seven members of the Korean Canadian community. In the first set, the subjects are standing in front of Lawren Harris’ painting Maligne Lake, Jasper Park (1924), facing outwards, and in the second set, they face Emily Carr’s Old Time Coast Village (1929–30), with their backs to the audience. The title refers to the year 1967, during which the Centennial of Canadian Confederation of 1867 was celebrated, and Canadian immigration restrictions were loosened. The title also references the Group of Seven, whose artistic legacy is the representation of Canada as a series of vast, uninhabited spaces. Yoon’s A Group of Sixty-Seven inserted Korean subjects into these inherited and idealizing narratives, questioning the very terms of inclusion in white-settler Canada.

In A Group for 2067, Yoon replaces the painted backgrounds of Harris and Carr with the greenery of the Maplewood Flats Conservation Area on Tsleil-Waututh lands. Yoon photographs the youth draped in fabric from the saekdong colours—typically seen on traditional Korean garments. In Korea, these colours presented together are associated with children, survival and resilience. Through these portraits of Korean Canadian youth, many of whom are bi-racial, A Group for 2067 renews A Group of Sixty-Seven’s call to create a new inclusive cultural imaginary of the country.

- Diana Freundl, Vancouver Art Gallery

A Group for 2067 (Pacific Flyways), 2022, 1 of 18 inkjet prints, 66 x 82.6 cm (26 x 32.5 inches) each

A Group for 2067 (Pacific Flyways), 2022, 1 of 18 inkjet prints, 66 x 82.6 cm (26 x 32.5 inches) each

A Group for 2067 (Pacific Flyways), 2022, 1 of 18 inkjet prints, 66 x 82.6 cm (26 x 32.5 inches) each

A Group for 2067 (Pacific Flyways), 2022, 1 of 18 inkjet prints, 66 x 82.6 cm (26 x 32.5 inches) each

A Group for 2067 (Pacific Flyways), 2022, 1 of 18 inkjet prints, 66 x 82.6 cm (26 x 32.5 inches) each

Becoming Crane (Pacific Flyways)

2022, chromogenic prints

With its subjects photographed against a background of oil refineries, at a bird sanctuary on the unceded territories of the Tsleil-Waututh Nation, Becoming Crane signals a shift from the politics of image to the politics of land. Implied by A Group of Sixty-Seven was the need for a new cultural imaginary, one that represented the land as fundamentally inclusive. In Becoming Crane, Yoon answers her own call.

Inspired by the migratory birds that move from one shore to another, these photographs portray youth of Korean ancestry, many of whom are biracial, carrying other histories in their bodies. Recouping the traditional Korean crane dance to depict diasporic subjects in flight, rather than attributing human characteristics to the birds, these performers attempt to do the opposite.

Through the work Yoon asks: “What models exist for non-colonialist possibilities of a different future?”.

- The Image Centre, Scotiabank Photography Award Exhibition

Becoming Crane (Pacific Flyways), 2022, (installation view), 106.7 x 162.6 cm (42 x 64 inches) each, The Image Centre. Photo credit: James Morley

Becoming Crane (Pacific Flyways) 1, 2022, chromogenic print, 106.7 x 162.6 cm (42 x 64 inches)

Becoming Crane (Pacific Flyways) 2, 2022, chromogenic print, 106.7 x 162.6 cm (42 x 64 inches)

Becoming Crane (Pacific Flyways) 3, 2022, chromogenic print, 106.7 x 162.6 cm (42 x 64 inches)

Becoming Crane (Pacific Flyways) 4, 2022, chromogenic print, 106.7 x 162.6 cm (42 x 64 inches)

Dreaming Birds Know No Borders

2021, single-channel video

In Dreaming Birds Know No Borders, a bird sanctuary on reclaimed brownfield land is connected to an estuary at the 38th parallel that divides the Korean Peninsula into North and South. Set within the unceded ancestral territory of the Tsleil-Waututh Nation, with a backdrop of the Trans-Mountain pipeline, a young man is seen moving meditatively, inspired by the traditional Korean Crane dance. This footage is intercut with images from a badly degraded VHS copy of a film made in North Korea in the 1990s about an ornithologist and his work, a man left behind when his family went South, permanently separated from them by the border of the DMZ (Demilitarized Zone). The orignal film score is played backwards as well as slowed down. Linking these two people and places, Dreaming Birds focuses on the poetic residue of longing– the unfulfilled desire of returning to a place you can’t.

Dreaming Birds Know No Borders, 2021, (video excerpts: 1min 49s), single-channel video, 7:22

Dreaming Birds Know No Borders, 2021, (video stills)

Untunnelling Vision

2020, photograph and video installation

Untunnelling Vision was filmed on location on Tsuut’ina Nation land previously leased by the Canadian Armed forces base in Calgary. This land was returned to the Tsuut’ina after 100 years, partially contaminated with live munitions from ‘war-play’. Ten years later, part of this land was cleared of mines and a movie set was erected– a place reduced to rubble by war– for shooting the Canadian war film “Passchendaele.” Following the filming, the set was left in place with the intention of turning it into a tourist destination. Using 360 degree video intercut with conventional video footage, Untunnelling Vision is set in an undetermined space and time, in which the historical and entangled relations between militarism, tourism and colonialism have played out.

Untunnelling Vision, 2020, (installation view), TRUCK Contemporary Art Gallery

Untunnelling Vision, 2020, (video excerpts: 1min 44s), single channel video, 21:26

Untunnelling Vision, 2020, (video stills)

Carrying Fragments (Untunnelling Vision), 2020, (installation detail), fabricated rocks and rubble, dimensions variable, TRUCK Contemporary Art Gallery

Saekdong Skies: Other Ways Through, 2020, (installation detail), inkjet canvases and birchwood, 185 x 74 x 80 cm, TRUCK Contemporary Art Gallery

Around the Ruins (Untunnelling Vision), 2020, inkjet print, 86.4 x 130.2 cm (34 x 52.3 inches)”

Capture: Picture in Progress (Untunnelling Vision), 2020, inkjet print, 109.2 x 145.6 cm

Upon the Wreckage (Untunnelling Vision), 2020, inkjet print, 86.4 x 130.2 cm (51.3 x 34 inches)

Untaken (sky exposure/land imprint), 2020, (installation view), silver gelatin prints, construction site, night sky, Dodge Ram 1500, 243.8 x 121.9 cm each, TRUCK Comtemporary Art Gallery

Rubble in Rubbleland (Untunnelling Vision), 2020, inkjet print, 50.8 x 67.4 cm (26.5 x 20 inches)

Rubbleland (Untunnelling Vision), 2020, inkjet print, 86.4 x 130.2 cm (51.3 x 34 inches)

Rubble (Untunnelling Vision), 2020, inkjet print, 66.7 x 55.3 cm (26.2 x 21.8 inches)

Mound (Untunnelling Vision), 2020, 2020, inkjet print, 47.1 x 58.4 cm (23 x 18.6 inches)

Living Time (Photographs)

2019, Series of 6 diptychs

Living Time, the two-channel video, is set on Hornby Island and explores how memory is carried in the body and passed on from generation to generation. The characters are visibly caught in different historical moments, blurring past, present and future. Through intercutting of live action and archival footage, the video explores different forms of recollection and remembrance, and nested temporalities that make time go on with no demarcations.

While the video marks time on a human level—psychically and affectively—the photographs convey it geologically. Here, photography is used to register human life in an instant. In the Living Time photographs the six diptychs portray each character as resilient yet fragile, connected yet displaced—shadowed within the landscape. Framing the lush West Coast setting with its immense trees featured prominently in each image, Jin-me Yoon presents the environment as something to be respected and revered.

- Diana Freundl, Vancouver Art Gallery

Living Time, 2019, Diptych 2, left image

Living Time, 2019, Diptych 2, right image

Living Time, 2019, (installation view), 6 diptych inkjet prints over-matted with custom Western hemlock frame, 71.44 x 76.52 x 3.81 cm each, Musée d’art de Joliette, photo credit: Paul Litherland

Living Time, 2019, Diptych 1

Living Time, 2019, Diptych 3

Living Time, 2019, Diptych 4

Living Time, 2019, Diptych 5

Living Time, 2019, Diptych 6

Living Time (Video)

2019, two-channel video

Memories haunt the characters of Living Time. For some, events are recalled, summoned by a simple gesture that effortlessly unites the spirit of the past with the physical body of the present. For others, memories have taken corporeal form, so tangible the body is locked in the past, and the spirit of the present made to bow to it. Through the intercutting of live-action footage and archival outtakes, Living Time explores different forms of recollection and remembrance and the nested temporalities that mark all of our lives.

Living Time, 2019 (video excerpt:3min 31s), two-channel HD video, 23:39

Living Time, 2019 and Touring Home From Away, 1998 (installation view), Musée d’art de Joliette, photo credit: Paul Litherland

Living Time, 2019 (video stills)

Long View (Photographs)

2017, series of 6 photographs

In Pacific Rim National Park Reserve on Vancouver Island, a hole is dug to unearth the layers of meaning—historical, touristic, emotional—sedimented in the memories so often muted by the beauty of open ocean and the endless horizon.

Long View, 2017, (installation view), 6 framed chromogenic prints, 83.8 x 141 cm each, Nanaimo Art Gallery, photo credit: Sean Fenzl

Long View 1, 2017

Long View 2, 2017

Long View 3, 2017

Long View 4, 2017

Long View 5, 2017

Long View 6, 2017

Long View (postcard edition), 2017, six perforated colour postcards, 10.1 x 15.2 cm (4 x 6 inches) each; 10.1 x 91.2 cm (4 x 36 inches)

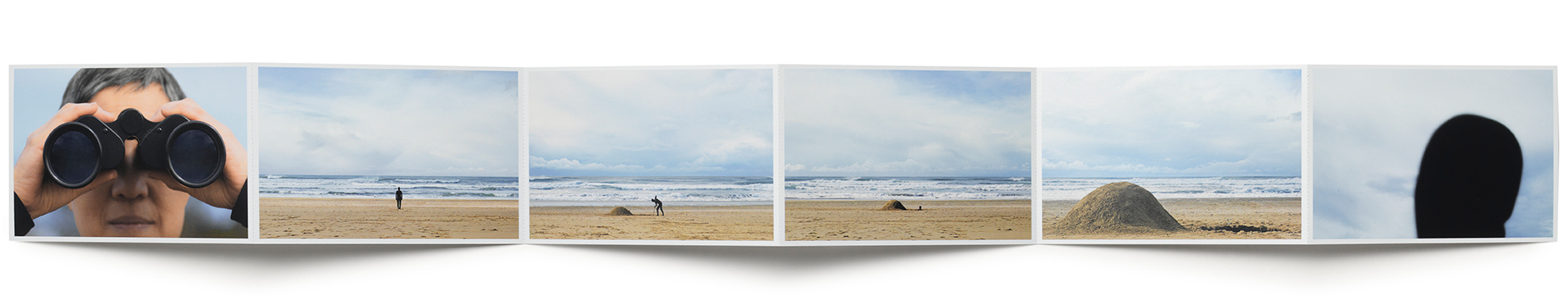

Long View (Video)

2017, single-channel video

Long View explores the historical, military, and personal threads that connect geographies on the Pacific Rim. All the characters in Long View regularly stop to scan the horizon, perhaps watching for potential threats, or simply letting their gaze drift longingly across the ocean to coasts on the other side of the Pacific. But when they dig a hole on the beach and the anonymous black-clad figure amongst them disappears into it, a different temporality takes hold. Archival images, dizzying camera movements and experimental sound signal a passage to an interior, memory-based reality. Past, present, and future; here and there; then and now are all caught in an undertow, swirling together in a disorienting montage that brings the site’s histories to the surface.

Long View, 2017, (video excerpts: 1:27), single-channel video, 10:03

Long View, 2017, (installation view), Nanaimo Art Gallery, photo credit: Sean Fenzl

Long View, 2017, (video still)

Long View, 2017, (video still)

Long View, 2017, (video still)

Long View, 2017, (video still)

Testing Ground

2019, single-channel video

Testing Ground was filmed on Long Beach, in Vancouver Island’s Pacific Rim National Park Reserve. Set against the background of the Pacific Ocean, soldiers move mechanically on the beach, suddenly multiplying like a colony of ants. When they abruptly disappear, they leave behind a few casual strollers along the water’s edge. The film is marked by an incongruity between the soldiers’ determined movements and the banal motions of ordinary passers-by, as if the scene is haunted by a restless memory. And in fact, it is: this same area was once used as a practice target for bombings, and while the Yuułuʔiłʔatḥ and t̓ukʷaaʔatḥ knows this land's history well, the touristic tide has washed away its traces.

- Anne-Marie St Jean-Aubere

Testing Ground, 2019, (installation view), Musée d'art contemporain des Laurentides, photo credit: Lucien Lisabelle

Testing Ground, 2019, (video still), single-channel video, 9:29

Testing Ground, 2019, (video still)

Testing Ground, 2019, (video still)

Other Hauntings (Dance)

2016, single-channel video, 8:14

Since 2007 a community of activists on Jejudo have vigorously opposed the construction of a naval base on a 1.2 km coastal lava rock called Gureombi, located near the village of Gangjeong… Sitting on a bench, a woman tells a story using her entire body as a map. Her dynamic gestures betray her background as a dancer, but she is not here to dance. She is a dedicated activist named Tera, who describes Gureombi and, through her words and gestures, becomes the rock. She argues that while the surface is broken, and the military base has been built, Gureombi is not completely destroyed; it remains alive underneath. As she speaks, an apparition in camouflage fatigues and long seaweed hair fades into view. This uncanny military presence takes over, but does not completely eclipse her. Like Gureombi she is lost from view, but she continues to have a voice.

– Jesse Birch

Other Hauntings (Dance), 2016 (video excerpt: 1:04), single-channel HD video, 8:14

Other Hauntings (Dance), 2016, (video still)

Other Hauntings (Dance), 2016, (video still)

Other Hauntings (Dance), 2016, (installation view), Nanaimo Art Gallery, photo credit: Sean Fenzl

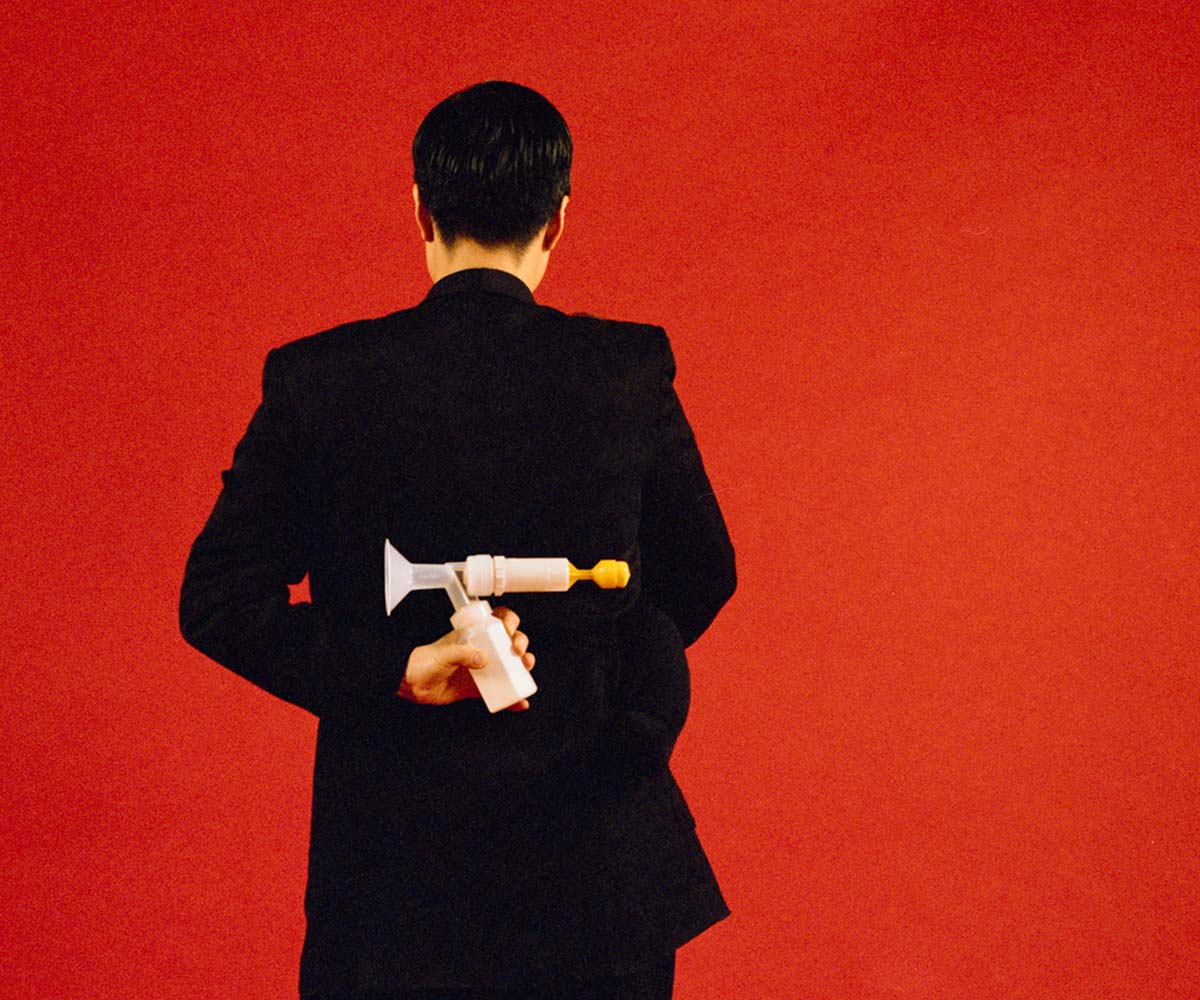

Other Hauntings (Song)

2016, single-channel video, 7:20

On Jejudo, the largest South Korean island protesters are not only against the increased military presence in the region, but also the destruction of the rock form called Gureombi: a sacred community prayer site, and an ecologically sensitive area containing fresh water springs and hundreds of animal and plant species… A trail system that once provided access to the entirety of the rock, now leads to a tiny remaining strip of Gureombi between the military base and a nearby resort. Community activists have remained vigilant to keep this small part of the rock safe from encroachment on either side. One of these activists is a catholic priest named Father Mun, who is a leading voice against the United States military presence in South Korea. Each day he sings a simple protest song to the military base that goes: 'Peace, Gangjeong, Gureombi, our love.'

Yoon’s camera follows a young man from Jejudo up the trail, past tourists and resort workers, to an outcrop where he too sings Father Mun’s song. But instead of singing to the remaining exposed part of Gureombi, he bypasses the concrete layer of militarism, and through an improvised device sings beneath the waves to a part of the rock that is only affected by geologic time.

– Jesse Birch

Other Hauntings (Song), 2016 (video excerpt: 1:44), single-channel HD video, 7:20

Other Hauntings (Song), 2019, (video still)

Other Hauntings (Song), 2016 (installation view), Nanaimo Art Gallery, photo credit: Sean Fenzl

This Time Being

2013, series of 9 chromogenic prints, varied dimensions

In this series of sculptural portraits, Yoon turns to the non-human world to reimagine relationality. A soft rubber sculpture is draped, hung, and propped in a variety of man-made natural environments, allegorizing dependency, interrelationality, and form. Creating a poetics of contingency, the works in the series This Time Being imagine a post-Anthropocene world in which humans rethink their primacy in the world. Yoon’s most abstract, formal work, This Time Being is an important highlight in her oeuvre, which indicates the central importance of constructed form in her work.

- Ming Tiampo

This Time Being 1, 2013, chromogenic print, 83.8 x 141 cm (33 x 55 1/2 inches)

This Time Being 22, 2013, chromogenic print, 45.7 x 55.9 cm (18 x 22 inches)

This Time Being 33, 2013, chromogenic print, 45.7 x 55.9 cm (18 x 22 inches)

This Time Being 44, 2013, chromogenic print, 45.7 x 55.9 cm (18 x 22 inches)

This Time Being 55, 2013, chromogenic print, 55.9 x 45.7 cm (22 x 18 inches)

This Time Being 66, 2013, chromogenic print, 45.7 x 55.9 cm (18 x 22 inches)

This Time Being 77, 2013, chromogenic print, 45.7 x 55.9 cm (18 x 22 inches)

This Time Being 88, 2013, chromogenic print, 55.9 x 45.7 cm (22 x 18 inches)

This Time Being 99, 2013, chromogenic print, 45.7 x 55.9 cm (18 x 22 inches)

Beneath

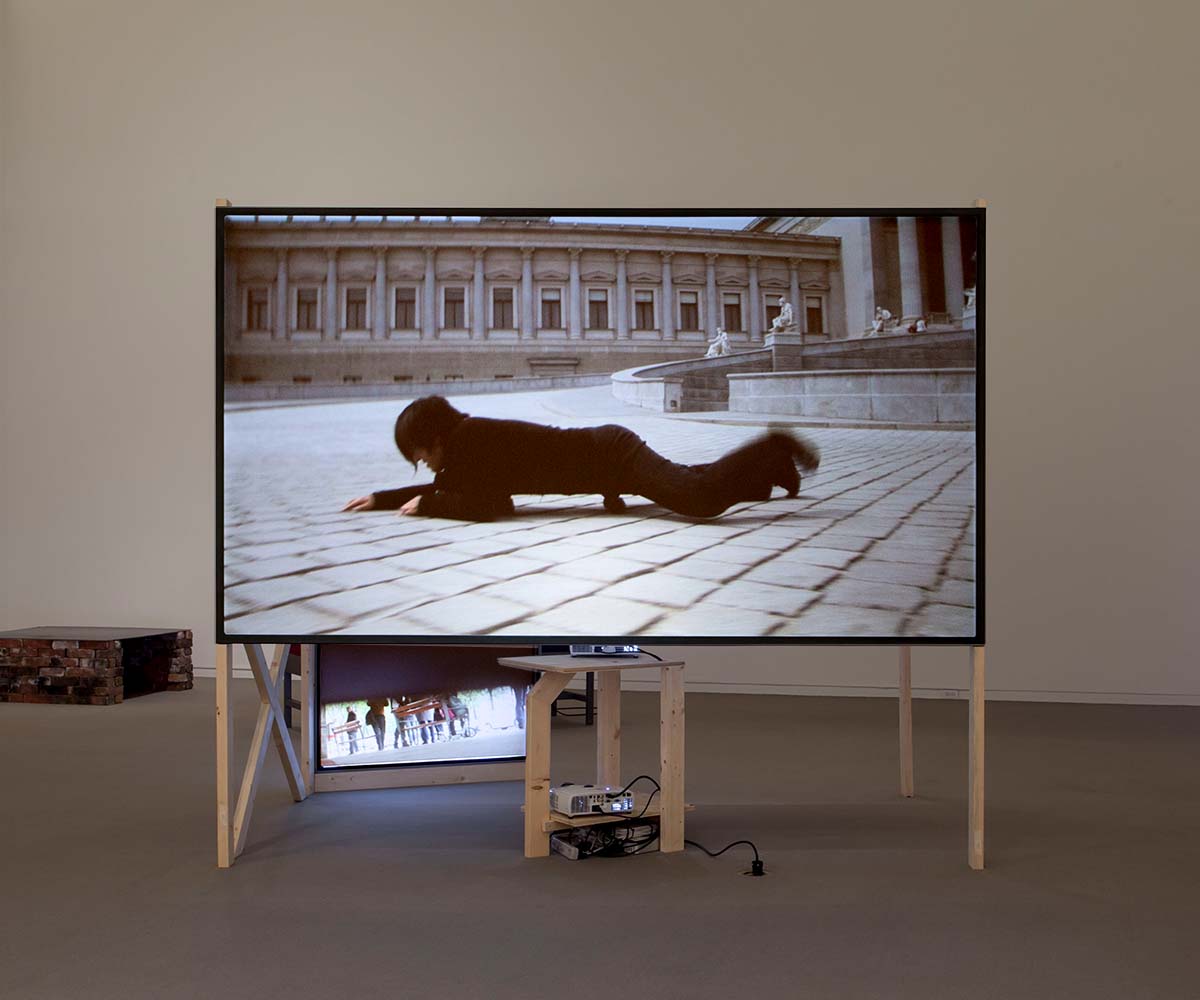

2012, multi-channel video installation

Beneath navigates a low path through Vienna—between Sigmund Freud’s former home and the site of his medical practice at 19 Berggasse and Heldenplatz, the centre of the former Habsburg Empire and the site where Adolf Hitler declared the Austrian Anschluß in 1938. Yoon uses her own body as a foreign presence within the city to forge a tangible link between the psychoanalyst’s fin de siècle Vienna and the social construction and politics of present day Vienna. While Beneath is deliberately left open to multiple references, there is a certain collapse that might be said to take place in this action, a refusal to resolve contradictions and artificially imposed boundaries between the intellectual and the visceral, the self and the other, the past and the present.

- Vancouver Art Gallery

Beneath, 2012, (installation view), multi-channel video installation, wood, glass, mirrors, steel and bricks, varied durations: 42:36 to 45:20, Vancouver Art Gallery

Beneath, 2012, (installation detail)

Beneath, 2012, (installation detail)

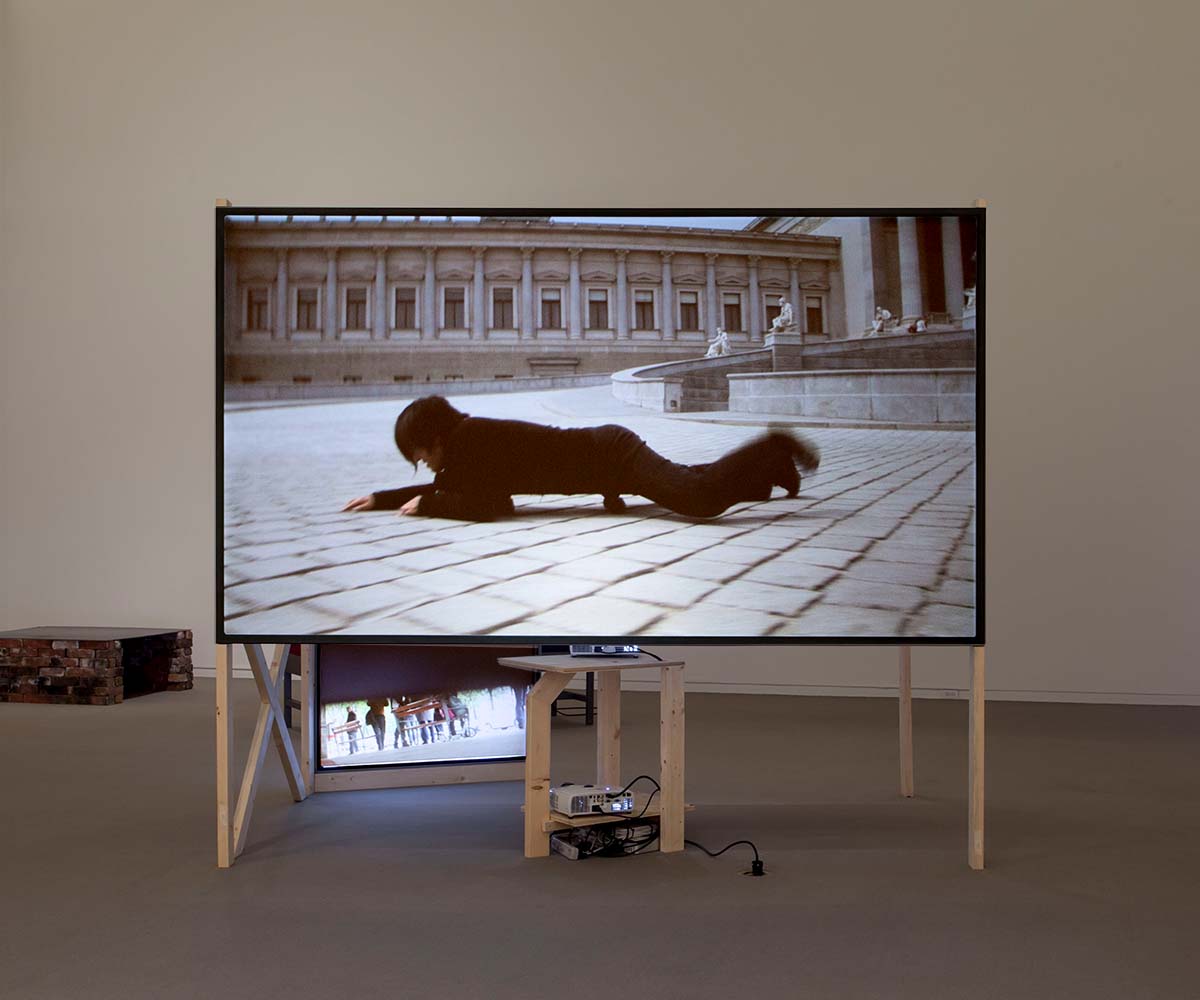

Time New Again

2010 / 2022, chromogenic prints, varied dimensions

In 2006, Jin-me Yoon began crawling along the ground on a moving platform in Seoul, Vienna, Vancouver, Beppu (Japan), Mexico City, and Nagoya, the industrial centre of Japan, where this photograph was produced. Here, spurred by a notion of progress and grounded in a staunch belief in science and technology, a messianic architecture gives form to an image of the 21st century.

In each of these places, from her horizontal, worm’s-eye perspective, Yoon sees the past’s aspirations for the future in the built environments before her. These are images of the progress envisioned by Japanese colonialism, American imperialism, European high modernism, and Canadian settler colonialism. From this position she also sees the oppressed bodies that enabled modernity to strive towards those images in the first place.

As we move through these haunted places, a question surfaces again and again: “How do we move forward from current conditions in the context of these inherited histories?”

Oasis 1 (Time New Again), Oasis 3 (Time New Again) and Oasis 2 (Time New Again), 2010/2022, (installation view), chromogenic prints, varied dimensions, The Image Centre, Photo credit: James Morley

Oasis 1 (Time New Again), 2010/2022, chromogenic print, 101.6 x 67.6cm (40 x 26.6 inches)

Oasis 2 (Time New Again), 2010/2022, chromogenic print, 101.6 x 152.4 cm (40 x 60 inches)

Oasis 3 (Time New Again), 2010/2022, chromogenic print, 101.6 x 152.4 cm (40 x 60 inches)

Levels 1 (Time New Again), 2010/2022, chromogenic print, 122 x 61 cm (48 x 24 inches)

Levels 2 (Time New Again), 2010/2022, chromogenic print, 122 x 61 cm (48 x 24 inches)

Watered Ground

2008, single-channel video

Water’s powerful ability to soothe both body and mind, thanks to its mineral properties, has made Beppu’s hot springs, especially those in the Kannawa District, a favourite healing place for the Japanese. After the Second World War, the city opened treatment centres to deal with the effects of the atomic bomb, taking full advantage of the region’s exceptional location on top of a geothermal hot spot. In this video, this humble communal outdoor bath is an inviting, relaxing environment where people can take a moment for themselves as well as socialize. Men and women occupy separate bathing periods, however the artist, a Korean woman, bathes with Japanese men. This innocuous gesture is one of monumental significance considering the sexual exploitation of Korean women—the history of comfort women —for example. The quiet coexistence of bodies in this context suggests a different path towards healing and reconciliation.

- Anne-Marie St Jean-Aubere

Watered Ground, 2008, (installation detail), Catriona Jeffries Gallery

Watered Ground, 2008 (video still)

As It Is Becoming (Beppu)

2008, single-channel video

The body, any body, walking through space has an associational field of meanings constituted through the relation of that body to its environment. These meanings, which include those of history, are considered to be stable or fixed. In response to this fixity, the artist has been experimenting with displacing the vertical, bi-pedal way we typically move through the world by giving it a horizontal orientation. Lying on a moving platform, Yoon performs lateral explorations (“crawling”) for the camera first through the city of her birth in As It Is Becoming (Seoul, Korea). She has performed similar actions in other towns and sites that differ in their geography, history and culture, performing acts of memorialization that nevertheless evade monumentalization. To date these cities and towns include: Seoul, Vienna, Vancouver, Beppu, Mexico City, and Nagoya.

As It Is Becoming (Beppu: Former U.S. Army Base), 2008, (video still)

As It Is Becoming (Beppu: Former U.S. Army Base), 2008, (installation view), single-channel video, 14:23, Catriona Jeffries Gallery

As It Is Becoming (Seoul)

2008, multi-channel video installation

In these lateral explorations, displacement is catalyzed as an artistic strategy causing these artworks to operate differently than a typical memorial: while a monument links an artwork directly and instrumentally to a historical event, in Yoon’s experiments, these links are indirect, requiring an artwork to pass through multiple and open-ended associations first. These associations are both historically concrete and abstract. Many of the sites in Seoul chosen by the artist have historical or personal significance. Thus the artist considers her works as a form of ephemeral and embodied commemoration of what bodies have endured, and often continue to endure, historically and at this present moment.

As It Is Becoming (Seoul), 2008, (installation view, Musée d’art contemporain des Laurentides), multi-channel video installation, dimensions variable, varied durations: 2:12 to 5:57, photo credit: Lucien Lisabelle

As It Is Becoming (Seoul), 2008, (video stills)

The dreaming collective knows no history

(US Embassy to Japanese Embassy, Seoul)

2006, single-channel video

The dreaming collective knows no history (U.S. Embassy to Japanese Embassy, Seoul) extends Yoon's interest in the interrelationship between the built environment of the city, history and the body. The first part of the title makes reference to Walter Benjamin’s suggestion that modernity and the flows of history are phantasmagoric. The second part of the title refers to the performance for the video on the street moving from the U.S. Embassy to the Japanese Embassy in Seoul. Formally tipping the vertical city of skyscrapers and bipedal humans onto a horizontal plane, alludes to the simultaneously submissive and subversive possibilities of this inversion. Rife in historical and contemporary references and associations, the smooth flows of progress and power as well as the frantic pace of production and consumption are interrupted.

The dreaming collective knows no history (US Embassy to Japanese Embassy, Seoul), 2006, (video still)

The dreaming collective knows no history (US Embassy to Japanese Embassy, Seoul), 2006, (video still)

The dreaming collective knows no history (US Embassy to Japanese Embassy, Seoul), 2006, (video still)

Fugitive (Unbidden)

2004, chromogenic prints

This transitional work features Yoon as a black-clad figure evocative of Hollywood ninjas or Viet Cong prowling through bamboo groves in Pioneer Park, Kamloops BC. These works were created in response to the 50th anniversary of the Korean War armistice, and explored how intergenerational histories of war are carried in the body. As such, the work operates on multiple levels. Firstly, it identifies the stereotypes imposed on Asian-Canadians and Asian Americans through popular culture, and explores how Asian subjects are constituted through one-dimensional portrayals in the media. Secondly, the work evokes the histories of war carried by Asian bodies and memories across oceans and continents before resettlement in Canada. Finally, put in relation to other histories of war and colonialism in the context of immigration to Canada, Unbidden speaks to the bodies unbidden to this land in order to evoke the power of solidarity and multidirectional memory.

- Ming Tiampo

Fugitive (Unbidden), 2004, (installation view, National Gallery of Canada)

Fugitive (Unbidden), 3, 2004, chromogenic print, 96.5 x 96.5 cm

Fugitive (Unbidden), 5, 2004, 1 of 3 in a series, chromogenic print, 76.2 X 76.2 cm

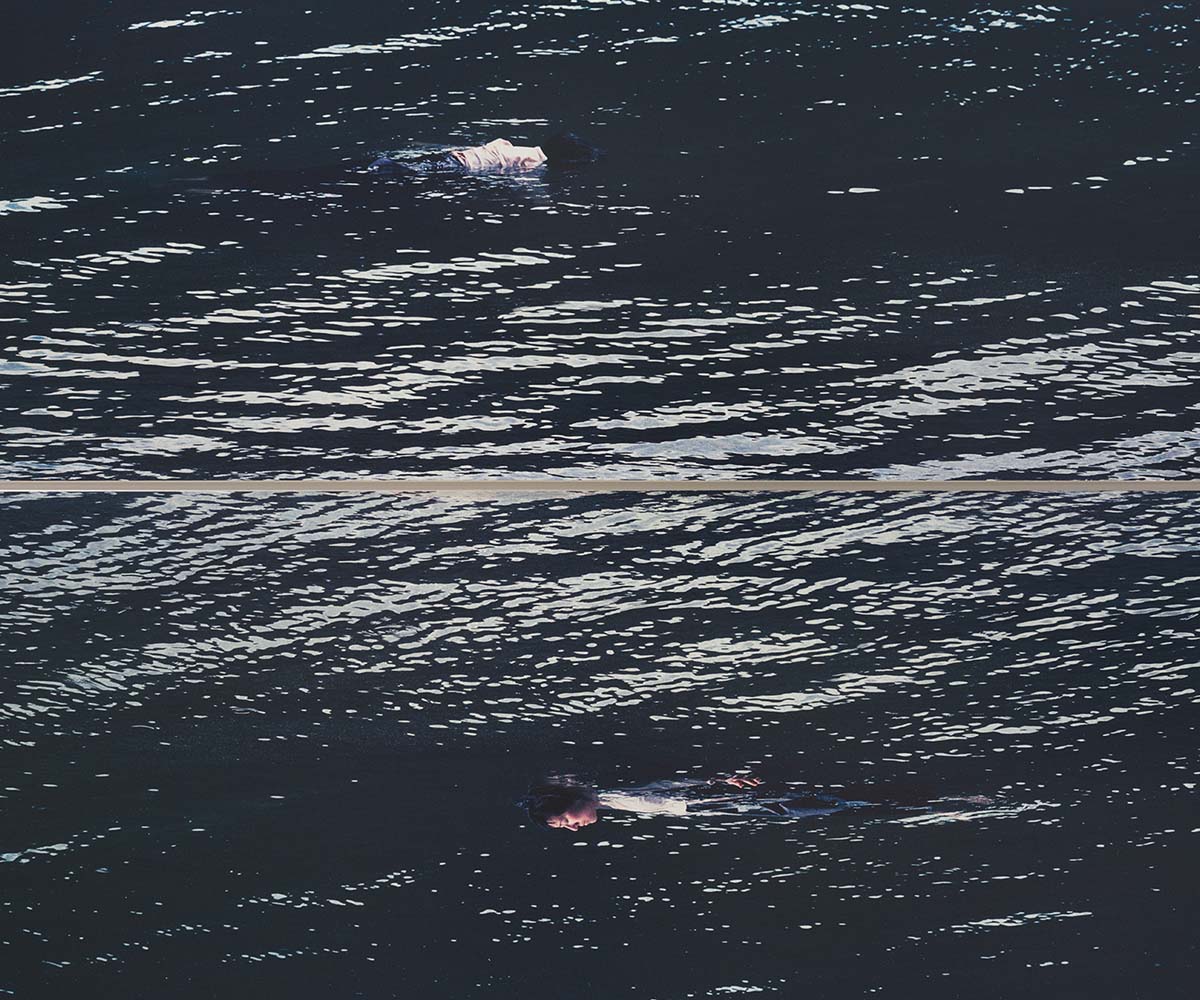

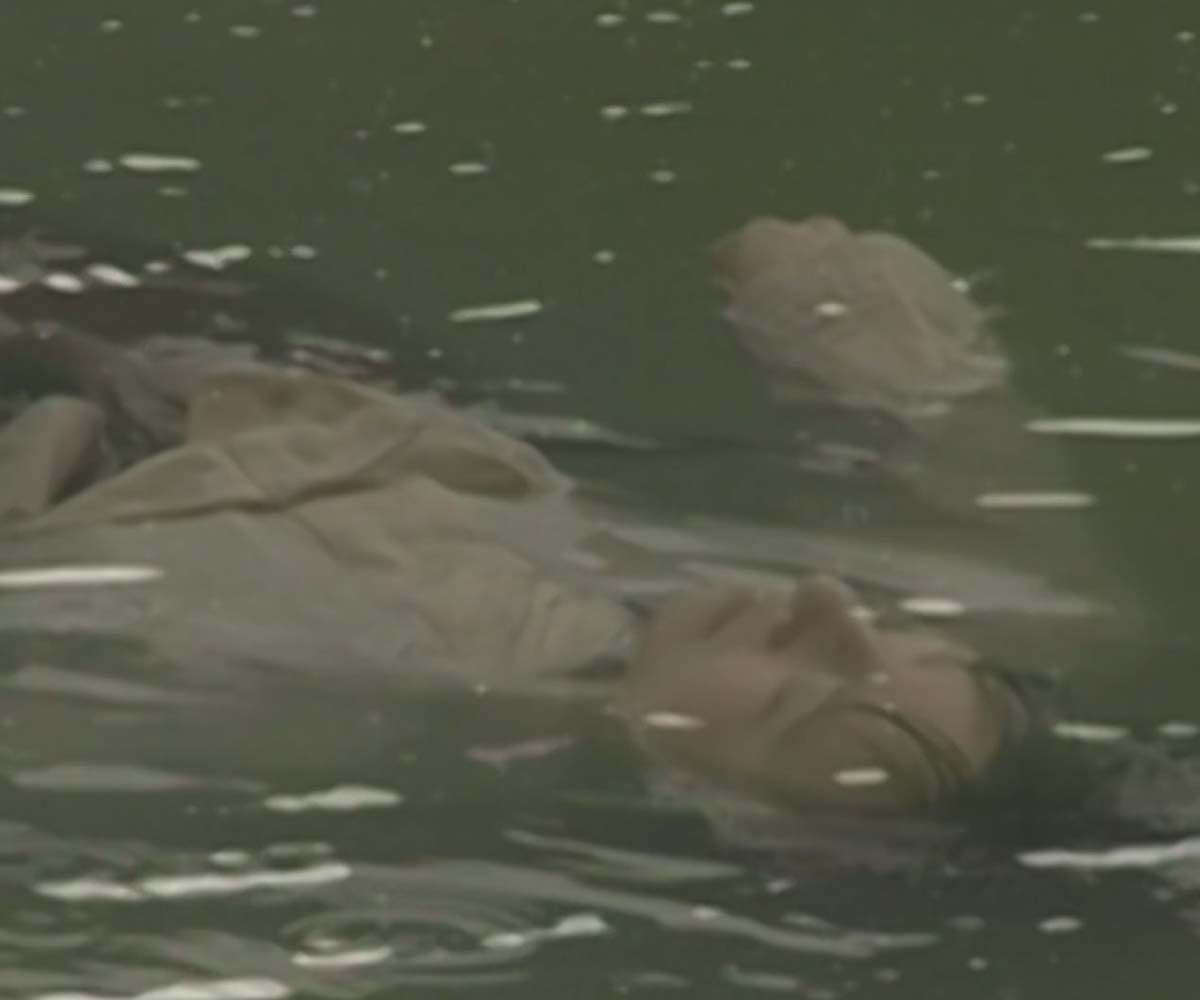

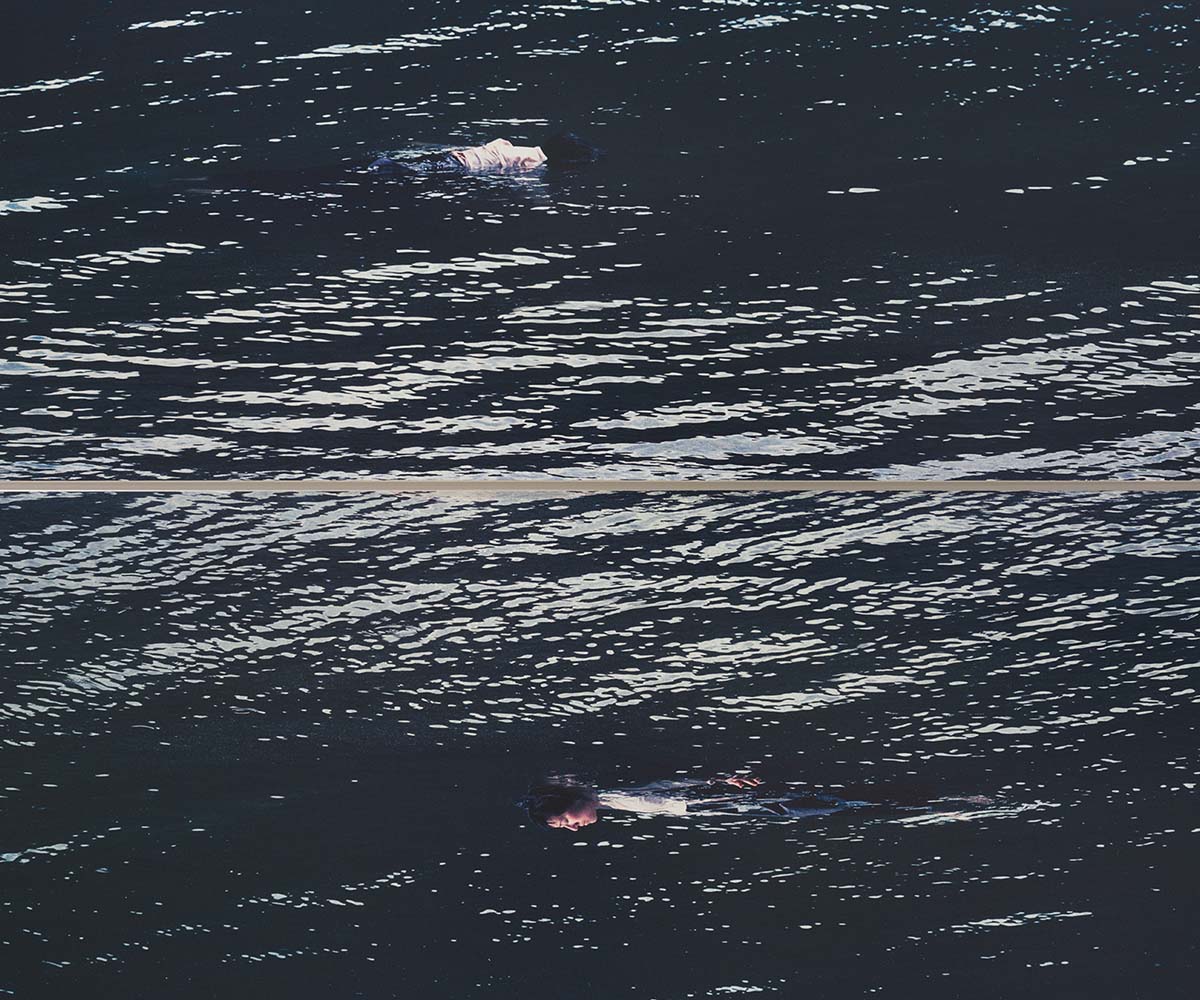

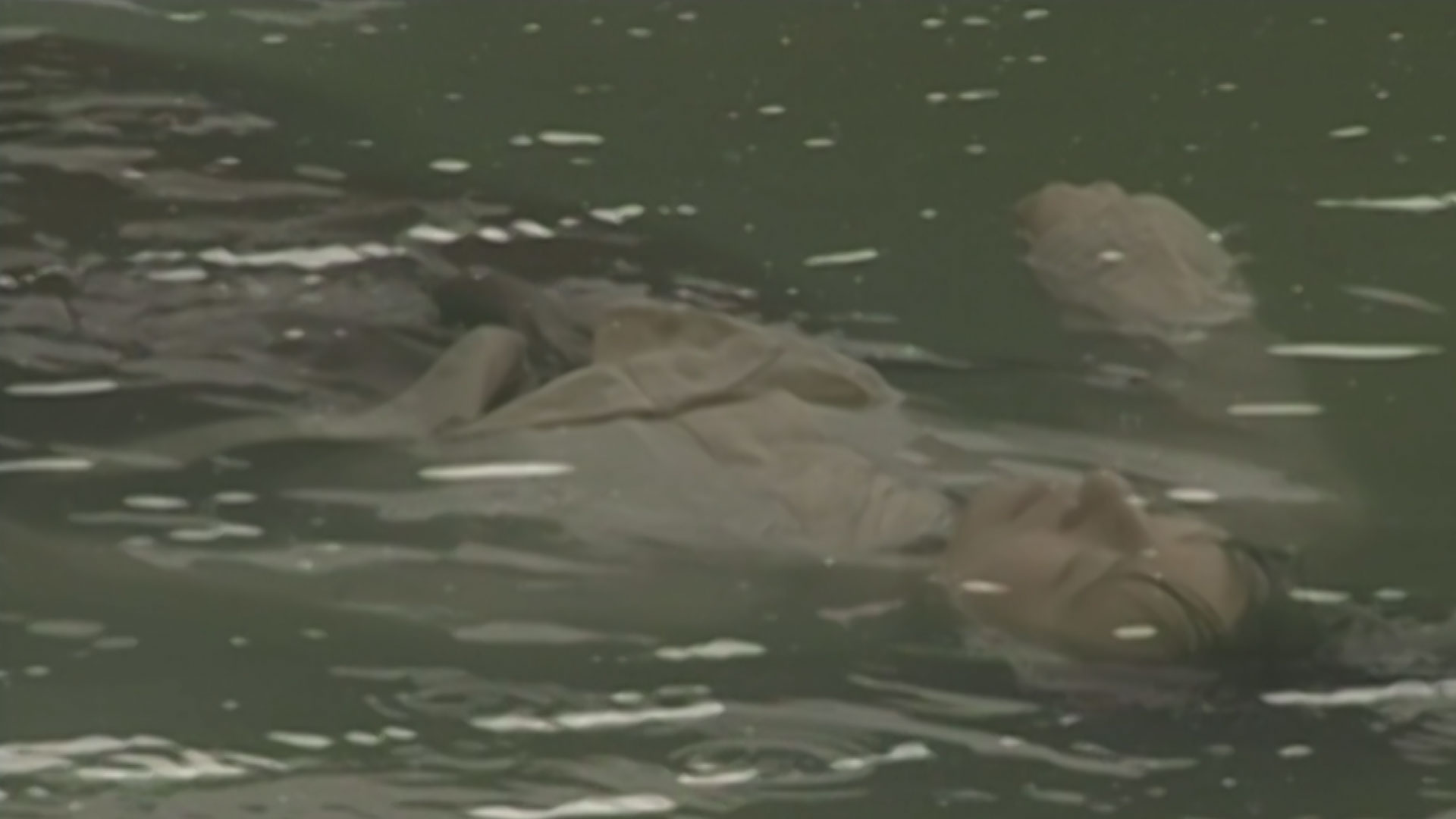

Unbidden (Channel)

2003, single-channel video

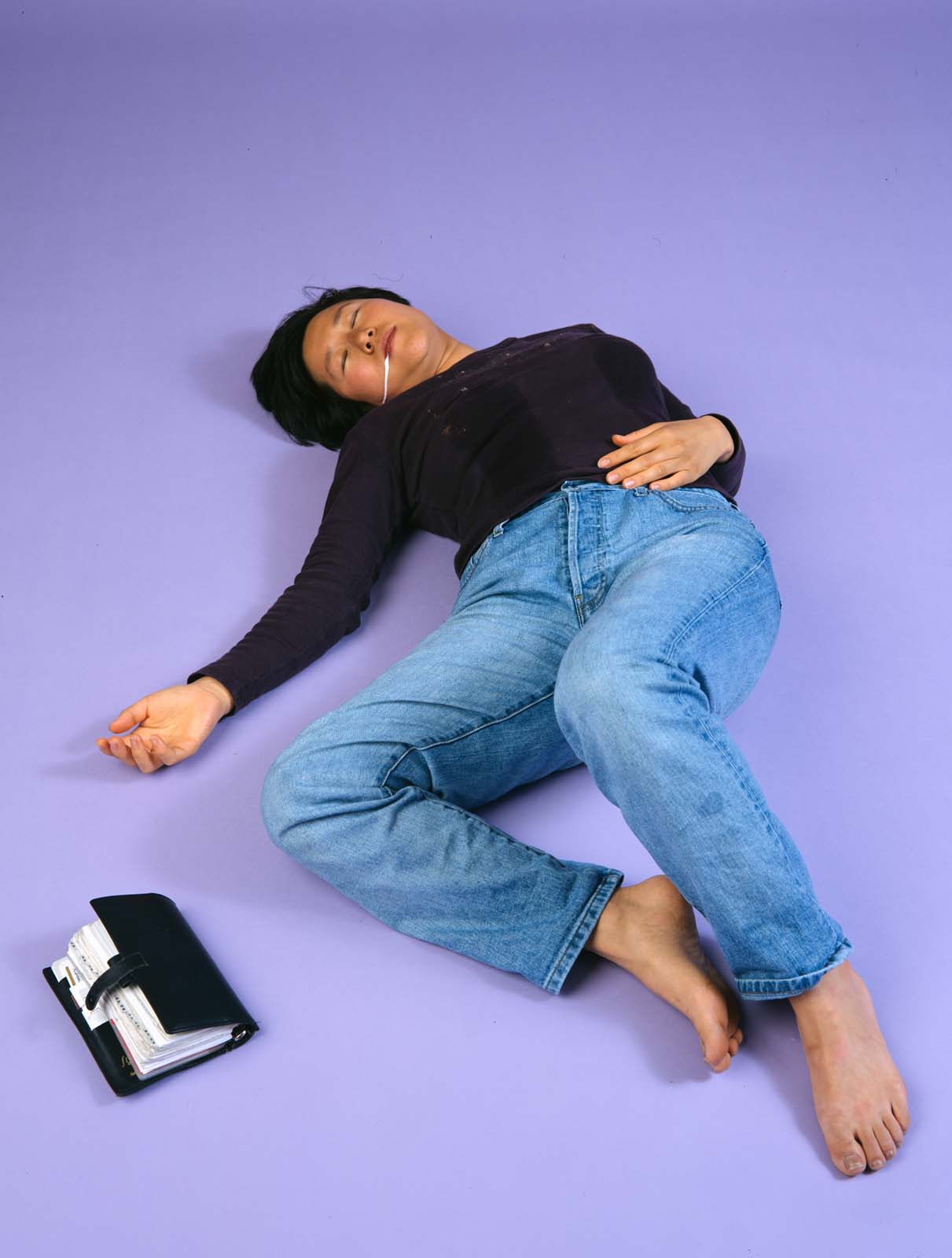

A figure dressed in traditional Korean clothing floats in what appears to be a river, perhaps the Han, but is in fact Paul Lake, near Kamloops BC. Two places merge into one, condensing several stories that follow the flow of memory. The body lies suspended, sinking then reappearing periodically to the rhythm of the water that sometimes submerges it completely. The play of superimposition and transparency creates the illusion of a ghostly presence, an intangible body on the edge of the visible and the invisible, of dreams and reality. Is this woman simply in repose? Or is her body a corpse drifting toward its final resting place?

- Anne-Marie St-Jean Aubre

Unbidden (Channel), 2003, (video still), single-channel video, 5:36

Unbidden (Channel), 2003, (installation view), photo credit: Lucien Lisabelle

Welcome Stranger Welcome Home

2002, single-channel video

In Welcome Stranger Welcome Home the central figure becomes a kind of avatar, a digital stand-in that travels through artificial worlds. Given that her role-playing presence is nonetheless the most stable element within this spectacle [the Calgary Stampede Parade], the piece seems to hold hybrid or unfixed identity as a fundamental condition (or maybe survival strategy) of places constructed in the cultural imaginary - such as the anachronism of a contemporary Canadian Wild West.

- Germaine Koh

Welcome Stranger Welcome Home, 2002, (video still), single-channel video, 8:46

Welcome Stranger Welcome Home, 2002, (installation view)

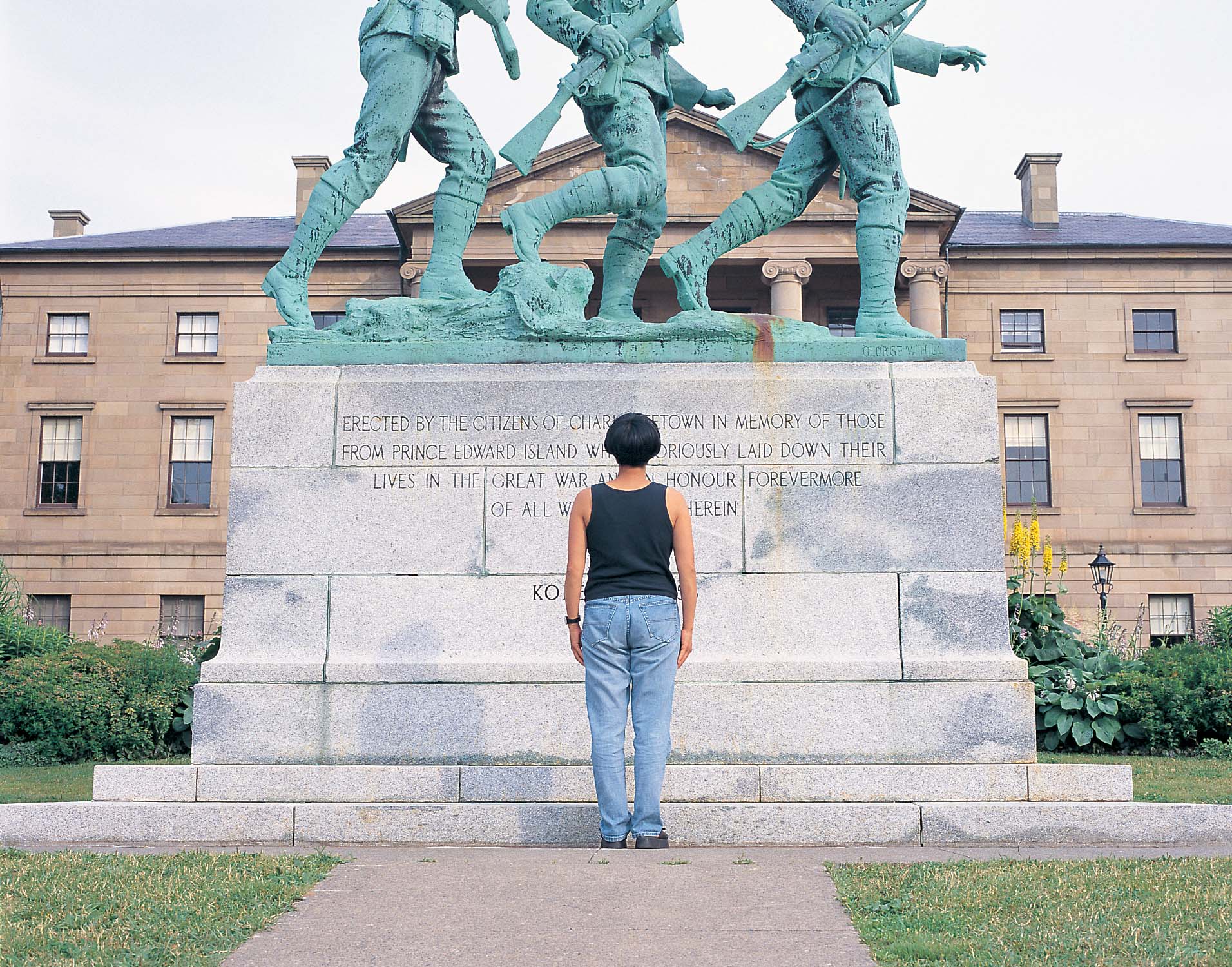

Touring Home From Away

1998, series of 9 diptychs (recto and verso)

The nine diptychs comprising Touring Home From Away are presented in double-sided lightboxes that resemble advertising panels. Created in Prince Edward Island, whose economy is based mainly on agriculture and tourism, the images create an entwined narrative that explores not only the island’s iconic sites and features—the house of the main fictional character in the novel Anne of Green Gables, a lighthouse, a potato field with its furrows of red earth—but also generic, everyday places: a convenience store, a Tim Hortons, an amusement park, and a superstore. The combination of these two types of imagery, staged photographs and imitations of family snapshots, undermines the idyllic portrait promoted by the tourism industry. By presenting the works recto-verso, the artist literally shows both sides of the images, playing on reversal to disrupt the narrative and reveal what often remains unseen.

Touring Home From Away, 1998, 1 of 9 diptychs (recto)

Touring Home From Away, 1998, 1 of 9 diptychs (verso)

Touring Home From Away, 1998, (installation view, Musée d’art de Joliette), series of 9 diptychs (recto and verso), black anodized double-sided lightboxes with ilfochrome translucent prints with polyester overlam, 66 x 81 x 13 cm each, photo credit: Paul Litherland

Touring Home From Away, 1998, 1 of 9 diptychs (recto)

Touring Home From Away, 1998, 1 of 9 diptychs ()

between departure and arrival

1997, two-channel video installation

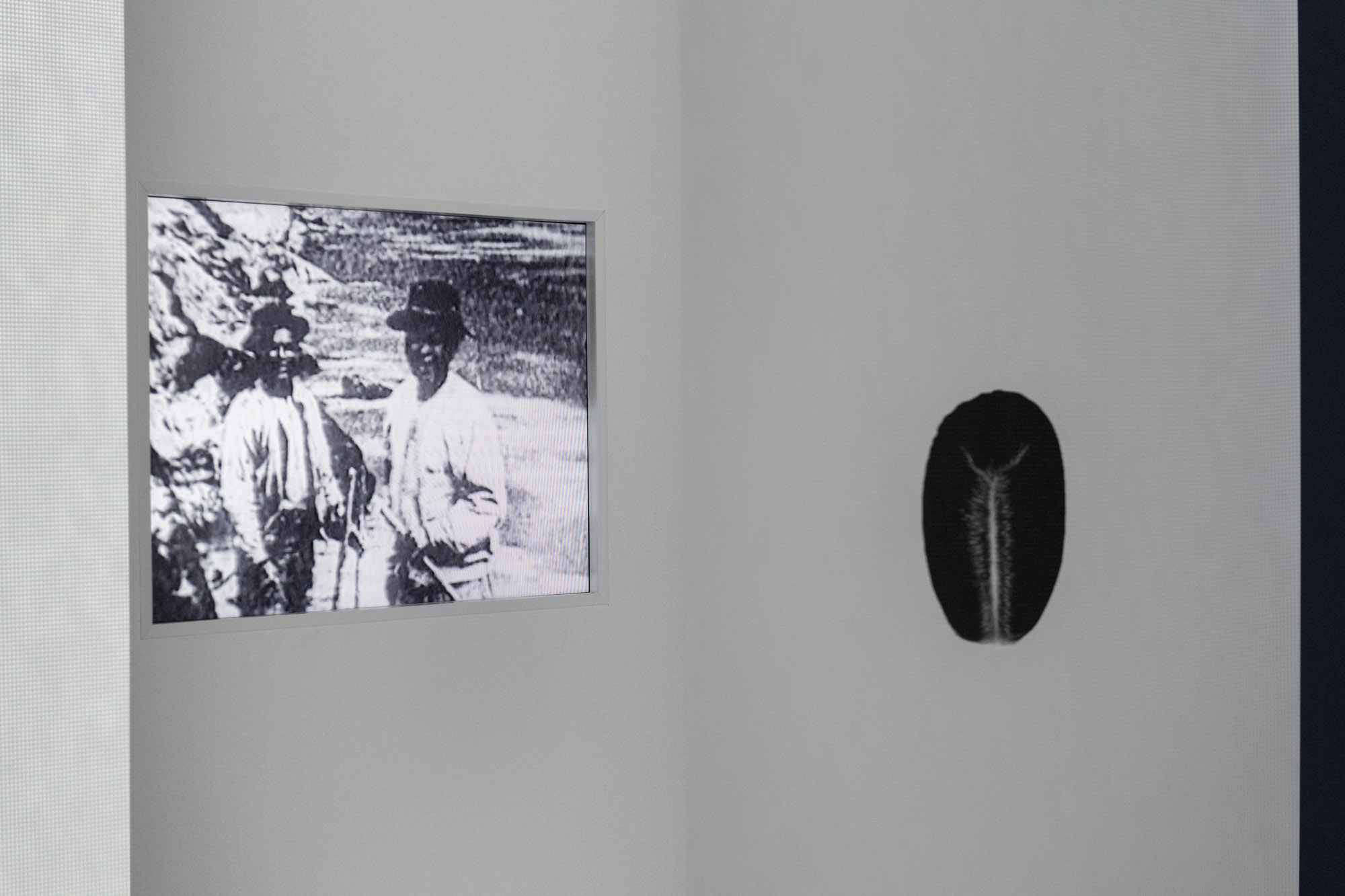

Between Departure and Arrival was Yoon’s first video work, and marked her entry into a practice which began to explore duration, time, history, and memory through the poetics of displacement. The relationship between history and the present moment is underscored through her use of archival film, taken from British Columbia’s provincial archives. Juxtaposing clips of Asian immigrants in Canada’s history with footage of clouds, as if seen from an airplane window, the work examines the deep and difficult history of Asian immigrants in Canada. Created in 1997, the year of the Hong Kong handover to China and a period of rising anti-Asian sentiment focussed on “monster homes” and who had the naturalized right to own land, Between Departure and Arrival probed questions of belonging, migration, and the complexities of national identity.

- Ming Tiampo

between departure and arrival, 1997, (installation view, Musée d’art de Joliette), two-channel video installation, print on mylar scroll, dimensions variable, 9:51, photo credit: Paul Litherland

between departure and arrival, 1997, (installation detail, Musée d’art de Joliette), two-channel video installation, print on mylar scroll, dimensions variable, 9:51, photo credit: Paul Litherland

between departure and arrival, 1997, (installation detail, Musée d’art de Joliette), two-channel video installation, print on mylar scroll, dimensions variable, 9:51, photo credit: Paul Litherland

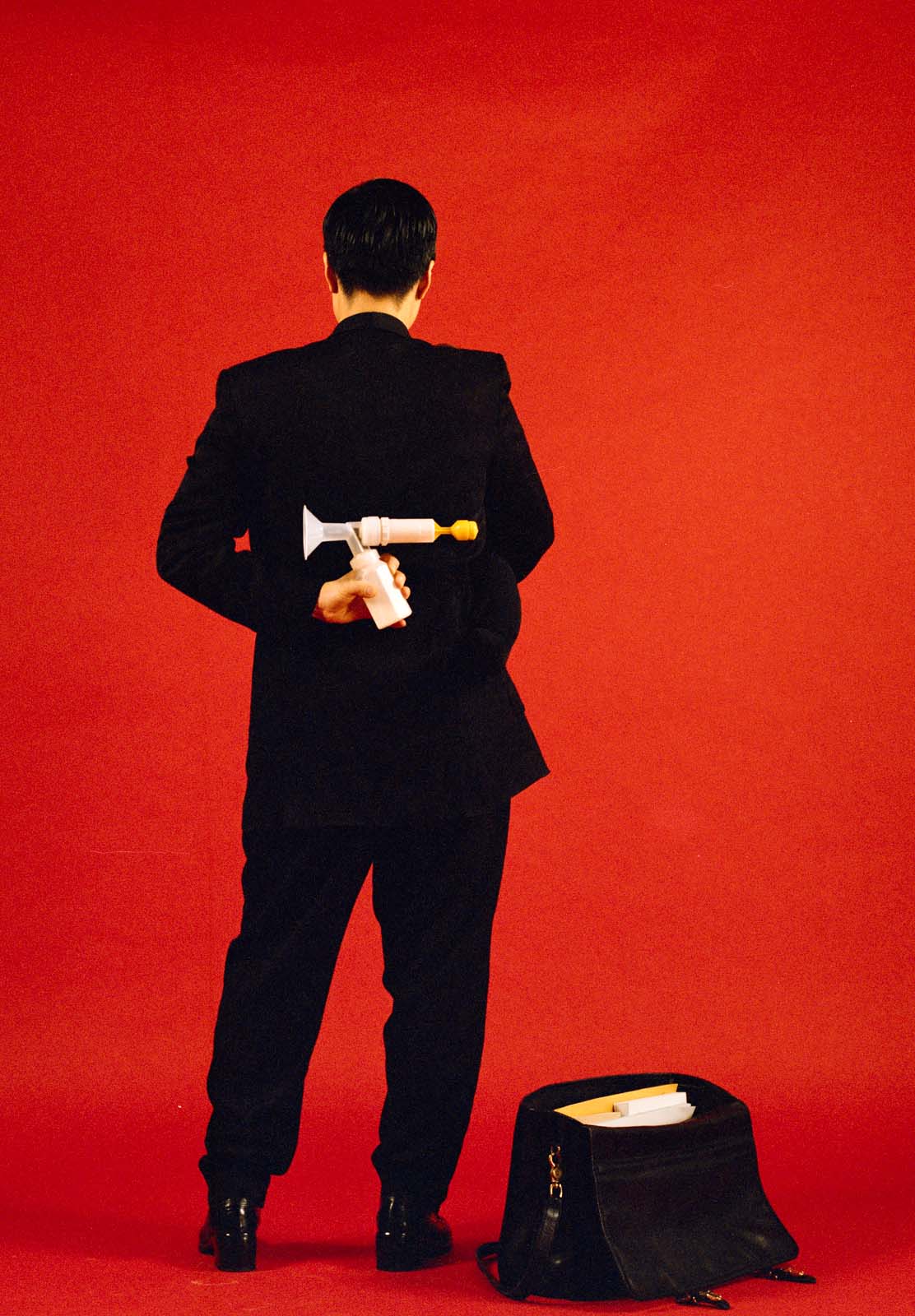

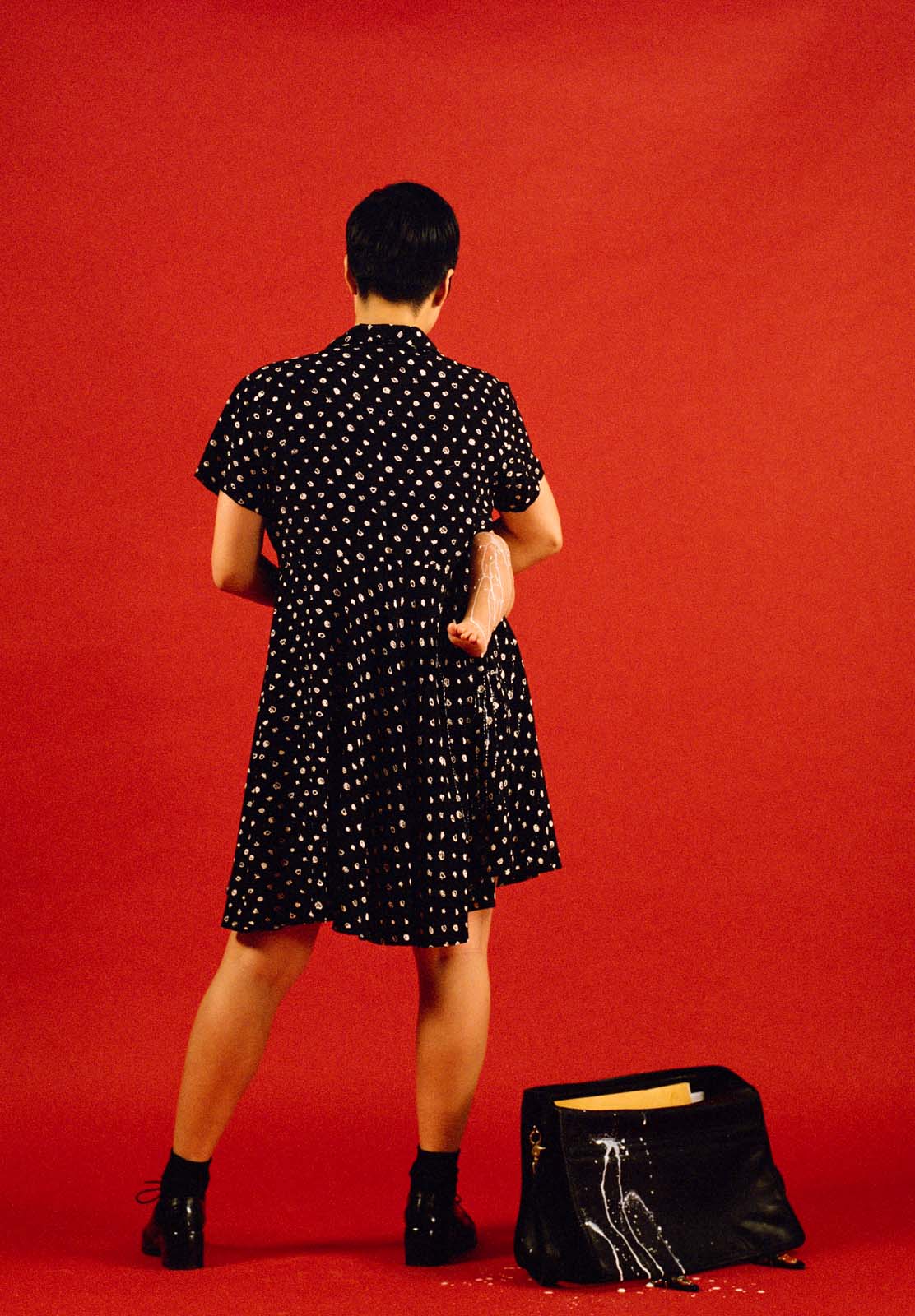

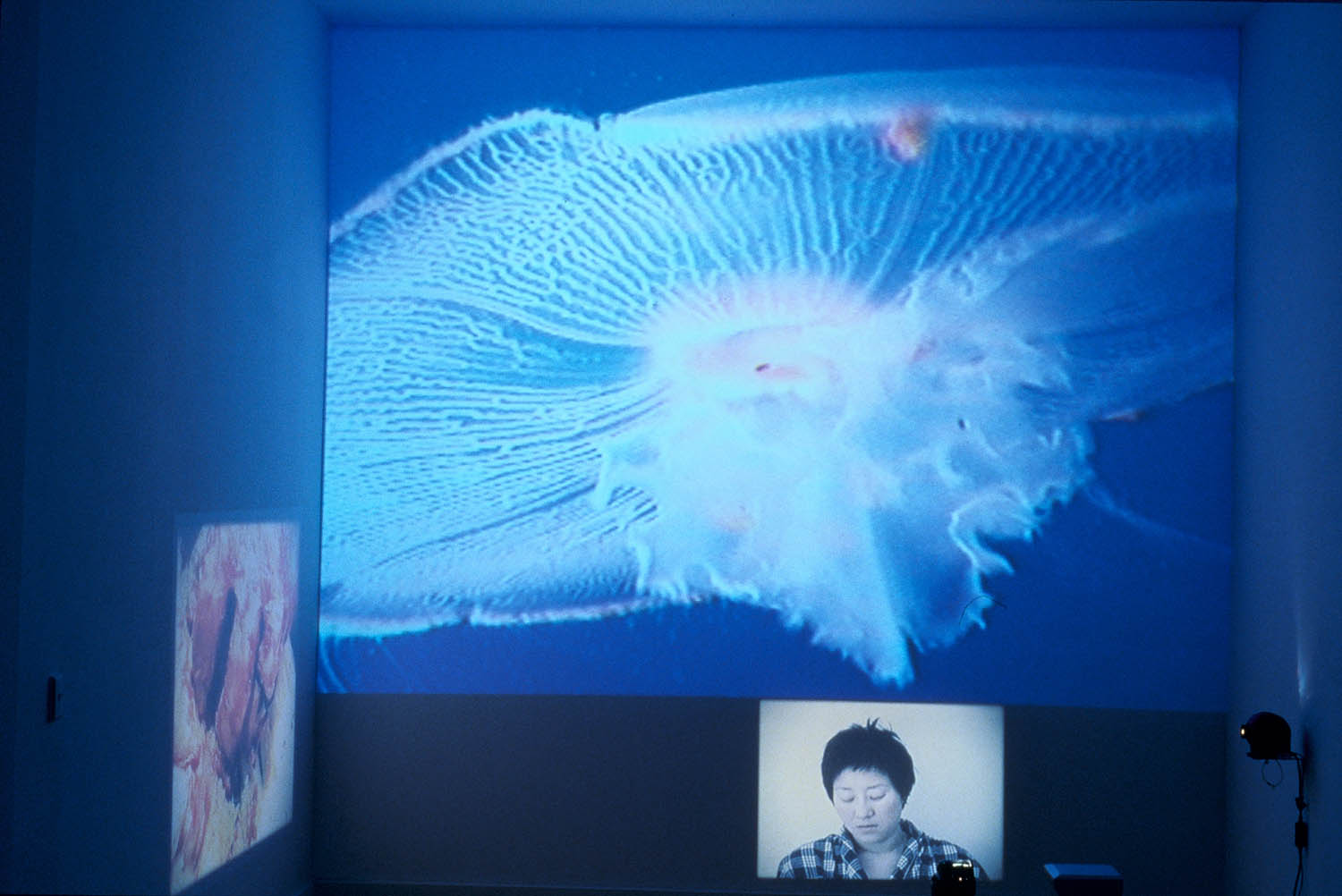

Intersection

1996 - , ongoing photo and video series

Yoon interrogates the maternal subject in this series, which will especially resonate well with mothers balancing work and child care in the midst of a pandemic. Set against richly coloured backgrounds that refer to advertising, Yoon’s use of “blatant artifice” addresses an important early context for her work—Vancouver photoconceptualism. Critically engaging with other predominantly masculinist practices—Abstract Expressionist drip painting, post-Duchampian practices and performance through a nod to Bruce Nauman’s Self Portrait as Fountain (1966)—Yoon asks: Can artist be both culturally productive and biologically reproductive? Can a racialized, feminist subject be an art historical subject?

- Ming Tiampo

Intersection 1, 1996, (installation view), diptych, chromogenic prints, 141 x 98 cm each

Intersection 1, 1996, (detail left panel), chromogenic print, 141 x 98 cm

Intersection 1, 1996, (detail right panel), chromogenic print, 141 x 98 cm

Intersection 2, 1998, diptych, (detail left panel), chromogenic print, 143.5 x 109.2 cm

Intersection 2, 1998, diptych, (detail right panel), chromogenic print, 143.5 x 109.2 cm

Intersection 3, 2001, diptych, (detail left panel), chromogenic prints, 207 x 161 cm

Intersection 3, 2001, diptych, (detail right panel), chromogenic prints, 207 x 161 cm

Intersection 4, 2001, (installation view), 3 single-channel video projections, dimensions variable

Intersection 5, 2001, diptych, (detail left panel), chromogenic print, 207 x 161 cm each

Intersection 5, 2001, diptych, (detail right panel), chromogenic print, 207 x 161 cm each

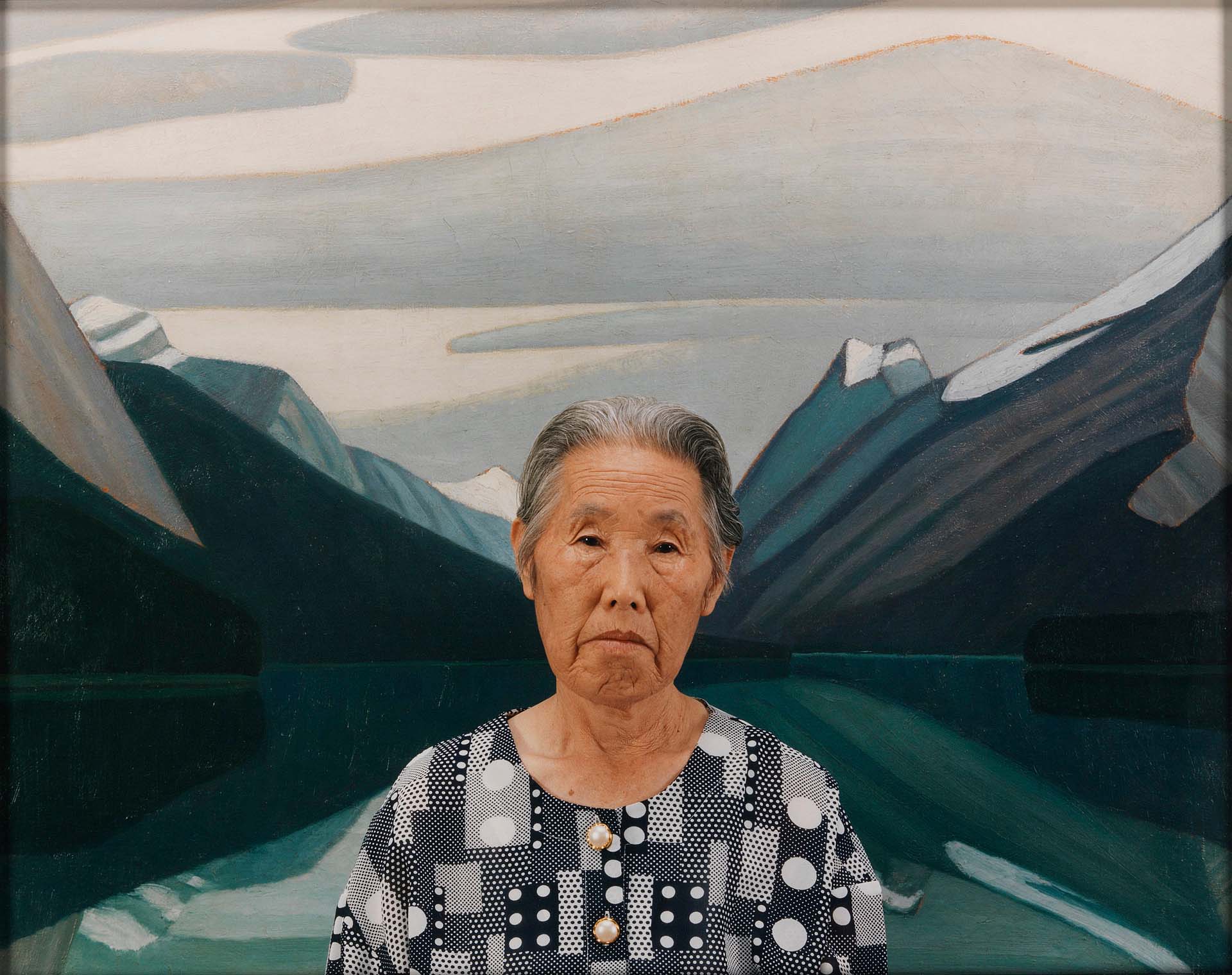

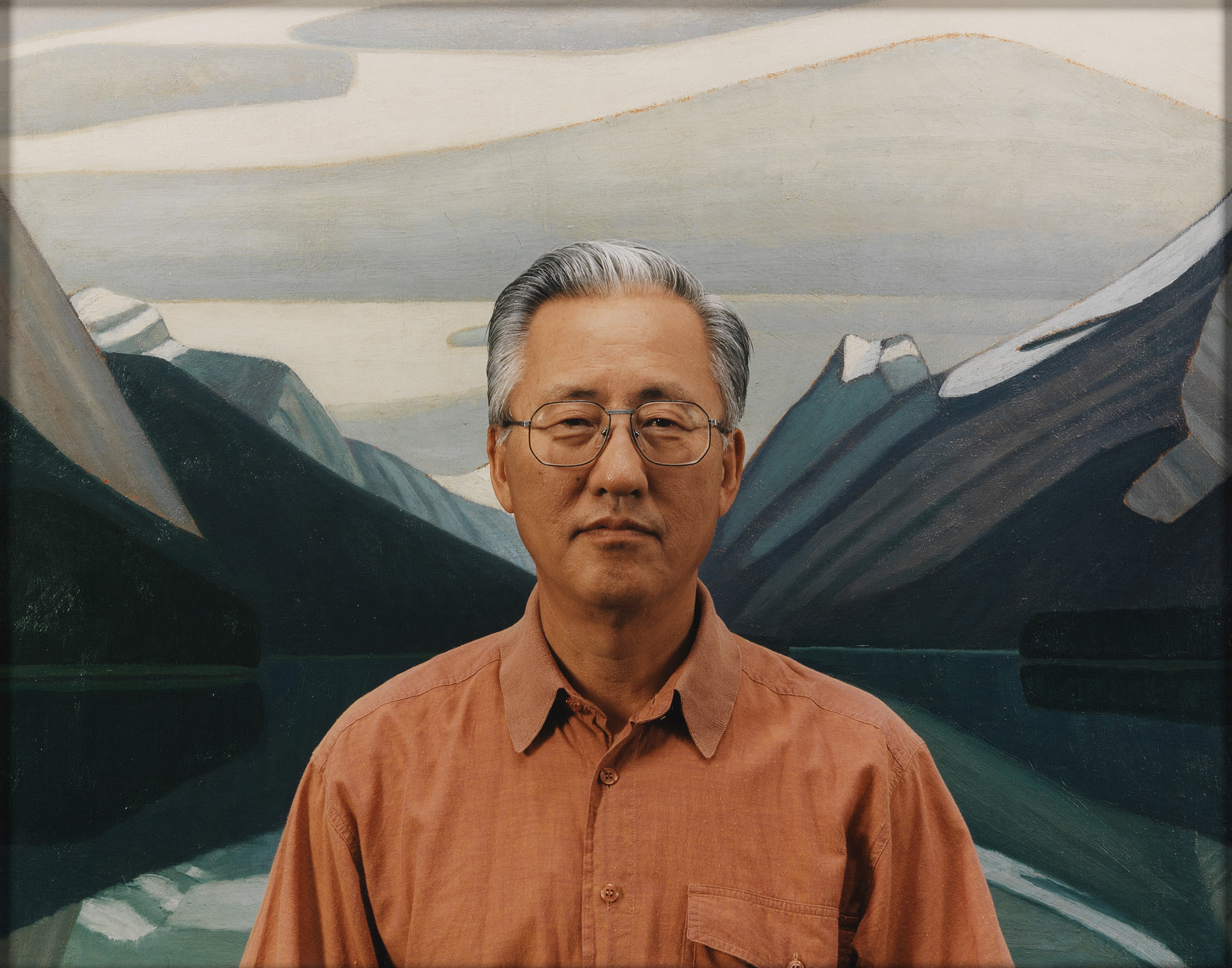

A Group of Sixty-Seven

1996, two grids of 67 framed chromogenic prints

Perhaps Yoon’s most iconic work, A Group of Sixty-Seven established Yoon’s position as a Vancouver photographer making conceptual interventions into the History of Art and representations of the nation. For this work, Yoon invited 67 members of the Korean-Canadian community to 3 separate Korean dinners at the Vancouver Art Gallery exhibition Art for a Nation. During that dinner, Yoon’s first experiment at the borderlands of conceptual photography and social practice, Yoon led a discussion about experiences of racism in Canada, and symbolically took formal portraits of all participants against two monuments of Canadian landscape painting in the VAG’s collection: Lawren Harris, Maligne Lake, Jasper Park (1924), and Emily Carr, Old Time Coastal Village (1924-30). Through these obviously constructed photographs (signalled through formal repetition), Yoon denaturalizes Harris and Carr’s colonial gazes on the landscape, the assumed disjuncture between immigrants of colour and that landscape, as well as the presumed documentary nature of the photograph itself. 1967 marked 100 years of confederation and the year restrictions were lifted on East Asian immigration to Canada.

- Ming Tiampo

A Group of Sixty-Seven, 1996 (detail)

A Group of Sixty-Seven, 1996 (detail)

A Group of Sixty-Seven, 1996 (installation view, Museum of Vancouver), two grids of 67 framed chromogenic prints for a total of 134 prints and 1 name panel, 47.5 x 60.5 cm each, photo credit: Rachel Topham

A Group of Sixty-Seven, 1996 (detail)

A Group of Sixty-Seven, 1996 (detail)

A Group of Sixty-Seven, 1996 (detail)

A Group of Sixty-Seven, 1996 (detail)

A Group of Sixty-Seven, 1996 (detail)

A Group of Sixty-Seven, 1996 (detail)

Honouring A Group of Sixty-Seven

1996/2021, inkjet prints, 66 x 165.1 cm (26 x 65 inches) each

This series emerged in the context of surging anti-Asian racism during the pandemic. Countering the xenophobic tendency to lump people together indistinguishably into target

groups, Yoon individuates the members of the community portrayed in A Group of Sixty-Seven, bringing their front and back together in a single frame and putting the name of the sitter into the

title of each photograph.

Made for the 25th anniversary of the earlier work, the series calls attention to the tradition of honorific portraiture in Korea and pays homage to the past. In a digital age of

constant change, we forget the past, but history and cultural traditions are our anchors—they ground us. Is there a way to embrace tradition without resorting to nostalgia and a static notion

of culture?

By attending to both contemporary and historical contexts, the portraits in Honouring A

Group of Sixty-Seven assume a diasporic understanding of the role the past can play, now and

for future generations.

Myung Choong Yoon (Honouring A Group of Sixty-Seven), 1996/2021, (installation view), inkjet print, 66 x 165.1 cm, The Image Centre, Photo credit: James Morley

Mi Ryun Rim (Honouring A Group of Sixty-Seven), 1996/2021, inkjet print, 66 x 165.1 cm

Sung Van (Honouring A Group of Sixty-Seven), 1996/2021, inkjet print, 66 x 165.1 cm

Chan-Sook Kim (Honouring A Group of Sixty-Seven), 1996/2021, inkjet print, 66 x 165.1 cm

Lin Ki Paik (Honouring A Group of Sixty-Seven), 1996/2021, inkjet print, 66 x 165.1 cm

Eun Kyung Chung (Honouring A Group of Sixty-Seven), 1996/2021, inkjet print, 66 x 165.1 cm

Souvenirs of the Self

1991, Series of 6 photographs

A set of six postcards that featured her wearing a Nordic sweater and jeans posing in front of a museum vitrine, a tour bus, Lake Louise, and other tourist sites, this series plays on the discomfort that her racialized body inserts into the national narratives staged in these postcards. With witty, ironic text on the postcard backs, Yoon unravels those narratives, and interrogates the representational claims made by museums, the tourist industry and photography itself, prompting the viewer to ask themselves who is Canadian? Whose land is this? As Monika Kin Gagnon writes, 'who is the rightful and naturalized national subject, especially given the ongoing history of colonization vis à vis the First Nations peoples?'

- Ming Tiampo

Souvenirs of the Self (Lake Louise), 1991/2019, (detail), inkjet print on laminated vinyl, 185.4 x 121.9 cm

Souvenirs of the Self (Banff Park Museum) , 1991/1996, chromogenic print transmounted to plexiglass, 243.8 x 182.9 cm

Souvenirs of the Self (postcard project), 1991, six perforated colour postcards, each 15.2 X 10.1 cm